Welcome!

I’m an architectural photographer and writer.

On my van-life travels through the British Isles I’m building up a word and photo-hoard of material culture that celebrates the value and distinctiveness of our built heritage and contributes to a sense of place.

My van is my time-machine, it gives me fresh perspectives on our remarkable places, shared here on a weekly basis. 📸🚐🏛

🏛 Missed the last Digest? Here it is.

🚐 View Digest Archive here.

Photo-hoard

I took this shot last weekend with the drone and inadvertently caught the act of spill-joy - that time when a wedding party bursts out of the west front after the formality of the nuptials.

Words

O Public Road…

You express me better than I can express myself

You shall be more to me than my poem.

You air that serves me with breath to speak!

You objects that call from diffusion my meanings and give them shape!

You light that wraps me and all things in delicate equable showers!

You paths worn in the irregular hollows by the roadsides!

I believe you are latent with unseen existences, you are so dear to me.

Song of the Open Road. Walt Whitman.

Observations

The Danish Invader

There’s no doubt that I’m imprinted by my vocation. Not just in the absorptive qualities of looking through a camera lens, but also there are times, especially when I’m travelling across country in my van, that my conscious eye, like my zoom lens, moves from the microcosm of the road to the macrocosm of the landscape beyond.

I often imagine the van from the heights of where my drone might spy me. From this viewpoint, I’m mindful of Alec Clifton-Taylor’s words describing the built landscape from above. In his book ‘The Pattern of English Building’ he views architecture visually rather than stylistically or chronologically. He whittles out a perspective of architecture based upon its pattern and materiality with chapters on stone, flint, the unbaked earths and thatch.

The first chapter describes the variety and character of our towns and cities, from an aerial perspective, rooted in the materials beneath them.

“About an hour after leaving London, red brick gives place to stone, grey, yellow or golden brown. Whether we have set out from Paddington or Euston, from King’s Cross or St. Pancras, whether we have followed the Great North Road, the Bath Road or Watling Street, we do not have to be very observant to notice the change. Sometimes it takes place quite suddenly; at others there is a moment of transition, as at Wheatley in Oxfordshire, where old buildings of grey stone are roofed with mellow red tiles, proclaiming the proximity of both stone and clay. But presently in all these directions the change occurs.”

This day I have photo shoots in several locations and I’m travelling with a heightened awareness of the landscape around me. The villages I pass through are of the earth - it’s as if the geology beneath has broken through the earth’s crust as an expression of architectural harmony. From my drone the villages are golden and textured and take on an organic plan not that dissimilar to lichen.

I travel through the great quarrying towns of Barnack, Collyweston and Ketton. They are all rooted in what lies beneath.

On the road, I’m caught up in the turmoil of the present times, my mind ruminating between gear changes, so I stop and pull out my map of the geology of Great Britain from the back of the van. This perspective makes me feel like an ant travelling across the geological borders from one millennia to another. When I pull the map down, fold it up and place it back in the recess at the back of the van, I notice another map - this time it holds a different set of boundaries. There’s one that encompasses large scathes of England like a blood red stain. This is a map of Anglo-Saxon Britain and the blood red stain is that of Danelaw.

My lens mind sets to work - it zooms out and then in on my location - I parry it with the map and notice that I’m heading towards another layer of meaning - this time the stratigraphy is historical - my final destination is once one of the five boroughs of Danelaw - once governed as a Danish Jarldom. On my geological map this town is predominantly yellow, from my historical map it is red; but, from the Great North Road that I’m travelling along, it takes on an ochre hue in the raking light. I find myself being transported from these transient times into these deep rooted layers of meaning.

In another book, Clifton-Taylor takes us from his birds eye view, past the Wheatley transition in Oxfordshire, down to the town that I can see intermittently between the gaps in the trees from my van on the A1. Of this place he says:

“Its mood is quiet; its colour, mainly a pale grey-buff, reticent. But it has great dignity.

I take the exit from the A1 with great excitement. The excitement is delayed by my phone’s battery failing along the A606. So I pull over into a pub ominously called the Danish Invader. I ask a chap if I’m on the right track.

‘Yes,’ he says. ‘Keep going along the road and head towards the spire.’

‘That’ll be my first destination,’ I say.

‘Welcome to Stamford,’ he replies.

Hotspots

Stamford

A huge thanks to digest member Jocelyn Chatterton for her generous help on what to do and see in Stamford.

I'm afraid I can't do Stamford any justice from one visit or even two.

Stamford is a kind of lodestar in the landscape, a hinge of geo-political, geological and historical borders and boundaries. Between the Danelaw and the Saxon, between the Liassic and the Oolite, between London and York. Its arterial plan and architecture is an expression of such profound roots.

I use a campsite near Stamford as my base for some satellite shoots and when I'm finished I head back to the town at every opportunity.

I find a home from home at the Crown Hotel at All Saints' Place and work out my itinerary.

First, I plan to visit its churches and then its streets and buildings.

Churches

Stamford is blessed with a medley of churches each with its own character. I didn't get the opportunity to visit them all but here's a few photographs of the ones that I did. All taken on iPhone.

St. John the Baptist.

Looked after by the Churches Conservation Trust. The joy of this church is the angel roof and the lively Victorian finials on the pews.

I pick up one of the CCT leaflets and some of the photos look very familiar - of St. Mary's in Higham, Kent. Taken when I were a mere lad.

All Saints.

The church has a delightful girdle of blind arcading - a syncopation that seems to pick up the repetition of devices in the Georgian buildings that surround it.

All Saints' church sits upon an island. A gothic island with delicious filtered views of the Stamford vernacular. Equally the views from the side alleys that surround the church are infilled with cusp and castellation perp and pinnacle.

I had little time inside - a wedding was due. Note the different styles of capitals to each arcade - different periods of construction.

The Early English stiff leaf capitals to the south arcade are Stamford chunky.

St. Martins

St. Martin's church lies to the south of the town across the river Welland. It holds the tombs of the Cecil family, notably William Cecil, Lord Burghley.

The tomb of John and Anne Cecil by Pierre-Étienne Monnot (1720's)

The tomb of William Cecil 1st Baron Burghley. (1590's)

Barn Hill

If Stamford were a cheese for the tasting, I'd push my corer into its ripened heart and pull out a section from Barn Hill. Barn Hill has all of the elements that contribute to the intangible spirit of a place. It has a mutual mix of vernacular and polite, texture and polish, wonky rooflines and teasing views and vistas. In a fit of laissez faire pique, to maximise my profit, I'd call my cheese Middlemarch, because parts of the series were filmed here.

The Buildings of Stamford

At university I picked up the knack of speed reading. It wasn't just a way of comprehending something faster - it also taught me about the rhythm and syncopation of the author. I've transferred this skill to speed scrolling through my photographs to try and capture the essence of a place.

If I scroll through my photographs of Stamford - the essence is largely classical with the odd intermission from a jettied building. There is a singular surprise of a brick building too that looks all the more striking in its oolitic surroundings.

There's more - Stamford has its own type of chunky and bullish classical architecture - it isn't as slender as Bath or Cheltenham - it's quite masculine. It didn't succumb to the craze of the fanlight. It is the town of the protruding architrave and the delightfully dramatic keystone.

Clifton-Taylor notes:

"It is evident that some of the builders enjoyed themselves very much in the treatment of keystones, which were arranged in a variety of different way, according to a variety of worked out rules. Some are single, some triple, some quintuple, one (13 Barn Hill) even septemtuple..."

I shall cherish the word: 'septemtuple' for the rest of my days.

Clifton-Taylor goes on to call the style a Jazzy Palladian, but for me the essence of Stamford is in one particular architectural trick which speaks volumes of its artisan roots.

Up and down the streets of Stamford are vernacular frontages where the asymmetrical reigns supreme - the jetty and the wonky eave - but they have been glossed with classical motifs and details.

Stamford through its architectural expression reveals a past that was once aligned with the great educational centres at Cambridge and Oxford contrasted against the evolving reality of a hard working, wealthy wool town.

Most buildings in Stamford are roofed from the slate at Collyweston and some are built in stone from Barnack. The finer ashlar oolite is from Stamford's own local quarries.

Shop Fronts

Doors

Stamford has a penchant for the decorated console bracket - swags and scrolls reign supreme.

Fanlight glass was traditionally cut from a circular roundel of glass blown and spun from a pipe. The glass in the door below is made up of the 'left over' centre of the roundel - the bit that's cut off from the pipe.

The rest of the glass was measured out (in inches) into sections and used in fanlights and windows.

I've fallen in love with Stamford and I'm already looking forwards to my next visit. I deliberately blinkered my interaction with the town - to have an excuse to come back.

In this digest I have not mentioned the delights of the Welland or the George Hotel or, for that matter the Burghley Estate - and, of course, many other churches. That will have to do for another visit and a later digest.

Vanlife

I stayed over at the Stamford Caravan Club Site which is a few miles out of Stamford.

But, in Stamford, I found myself another place to work - a room with the same snug-like proportions as my van. I bobbed in and out for refreshments and the odd bitter-shandy - to catch up with the digest work and review the logistics for the next shoot.

I walked past it at first. The establishment didn't seem to have a name - but the darkened rooms within, and the chatter and bonhomie beyond, drew me in.

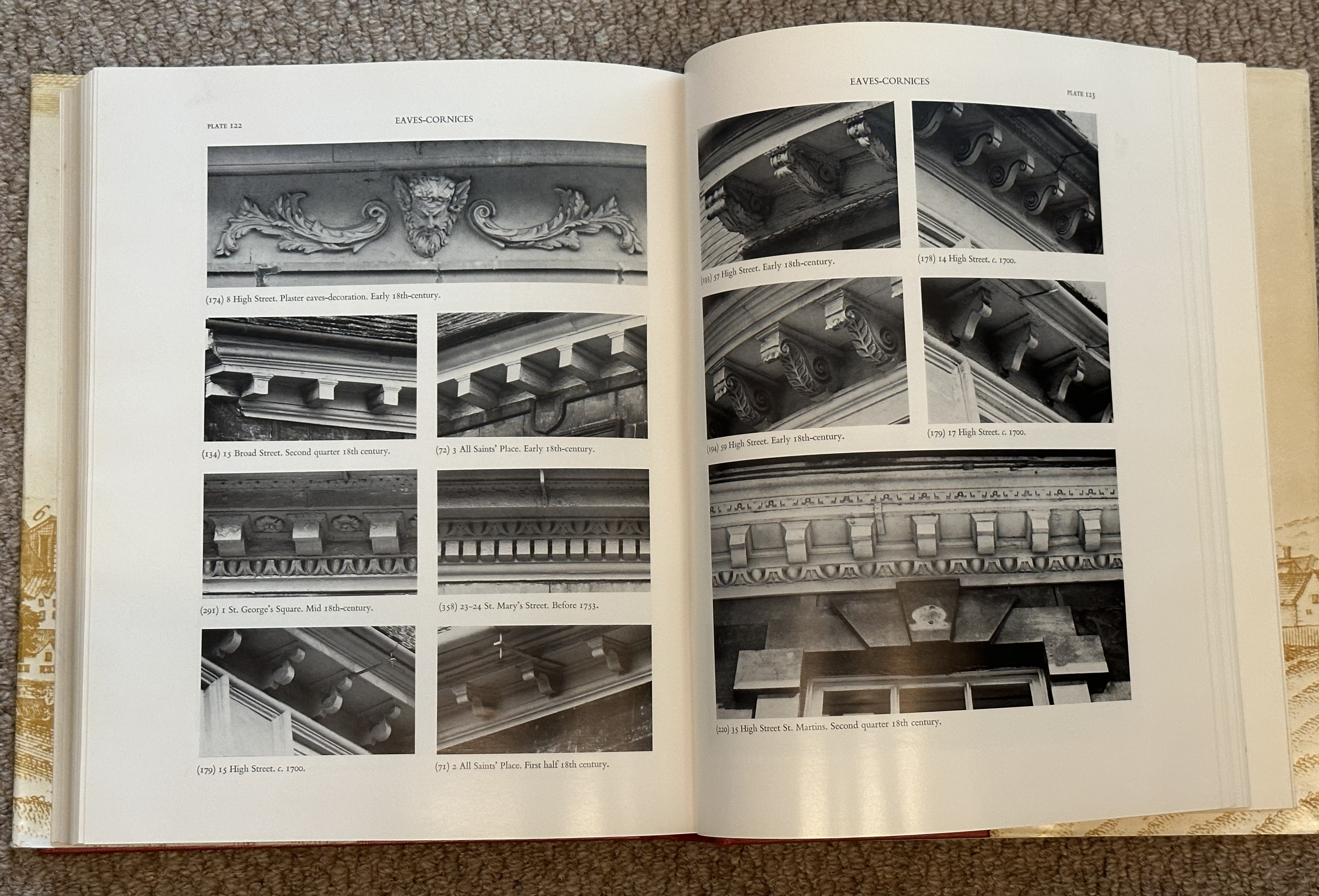

On My Coffee Table

From The Charo's

Bookmarked

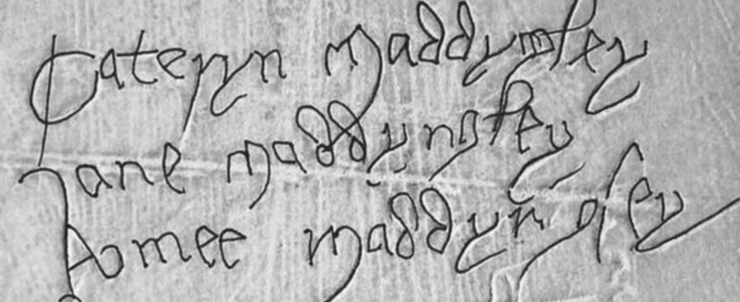

Cambridgeshire church plague graffiti reveals 'heartbreaking' find - BBC News

Hidden "heartbreaking" graffiti discovered in a Cambridgeshire church reveals how three sisters from one family died in the same Tudor plague.

Country diary: Quarries dot the coastline over the milky blue Channel | Coastlines | The Guardian

Purbeck, Dorset: Rooks caw and peck at the turf; reddish-brown cattle lie facing the south-west wind and the distant Portland Bill

Film and Sound

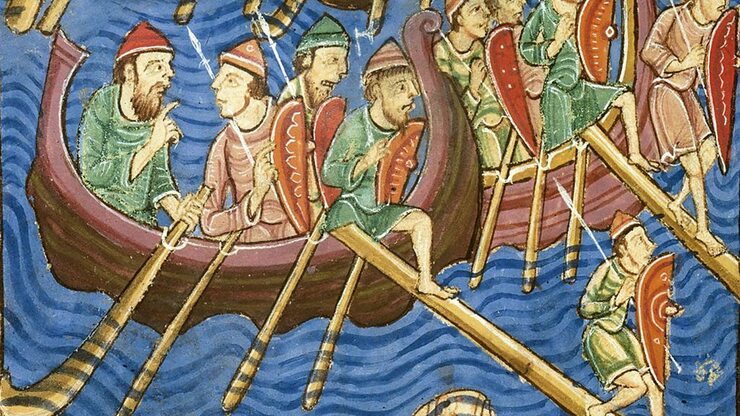

In Our Time - The Danelaw - BBC Sounds

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the effective partition of England in the 880s after a century of Viking raids, invasions and settlements. Alfred of Wessex, the surviving Anglo-Saxon king and Guthrum, a Danish ruler, had fought each other to a stalemate and came to terms, with Guthrum controlling the land to the east (once he had agreed to convert to Christianity). The key strategic advantage the invaders had was the Viking ships which were far superior and enabled them to raid from the sea and up rivers very rapidly. Their Great Army had arrived in the 870s, conquering the kingdom of Northumbria and occupying York. They defeated the king of Mercia and seized part of his land. They killed the Anglo-Saxon king of East Anglia and gained control of his territory. It was only when a smaller force failed to defeat Wessex that the Danelaw came into being, leaving a lasting impact on the people and customs of that area.

From the Twittersphere

Response

Treasure Hoard Gazetteer

Andy Marshall’s Treasure Hoard Gazetteer Map

My Treasure Hoard Map is open to all. It is an evolving enterprise and I’ll be adding more entries as time passes.

View the full map on Google maps

View the full map on Google Earth (recommended)

More on the Treasure Hoard Gazetteer

Thank You

Thanks to all subscribers for your continued support

Thanks to Patrons and Members for helping keep the Genius Loci Digest free and public facing.

And Finally

Found in St. John the Baptist, Stamford. If you're a writer - a great name and occupation for a protagonist.

My Linktree

Member discussion