Camper-van-camino Edition

In Pursuit of Spring continues...next week

More on this project here

⚡️ View the latest digest and the full archive here.

📐 My Goals ℹ️ Donations Page & Status 📸 MPP Status 🛍️Shop

🔗 Connect with me on: Bluesky / Instagram / Facebook / X / Tumblr / Flickr / Vimeo / Pixelfed / Pinterest / Flipboard/ Fediverse: @fotofacade@digest.andymarshall.co

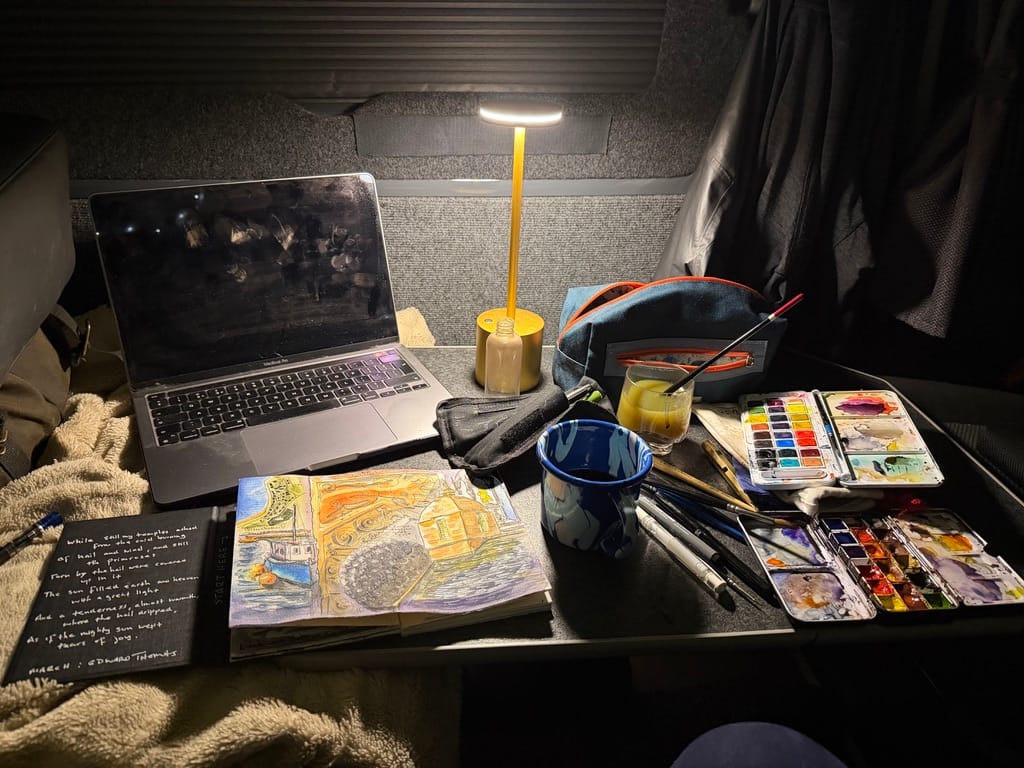

After spending the evening writing up my digest post and finishing the day’s watercolour, I have a fitful sleep. In the middle of the night I wake convinced that my winter duvet has slipped off me. It is excruciatingly cold. I look down into the darkness of the van - I am still covered.

I switch on the diesel heater. After a few minutes the screen flashes an error code. I look it up. The diesel has thickened in the cold and is blocking the fuel lines.

It is one of the coldest mornings I have had in the van. It feels like an effort simply to get up and get moving - to wind in the electric hook-up, clear the windscreen, and negotiate the snow-covered roads. But gradually it gets done. The engine settles and the glass clears. Then, slowly, the day begins to show itself in the rising sun.

I’m hoping upon hope to escape the jaws of winter and find something of spring as I travel towards Cornwall.

Follow this journey on my WhatsApp channel.

I'm travelling the length of the country in pursuit of spring, but this first week has only showed me the tail end of winter.

Here is the story so far. I've included yesterday's observation here first - which hasn't been posted out until today.

"Would you lean your back

against me cutter?

Would you rest your axe

a while and sleep?

Listen to the song I utter

Hear my heartwood weep."

- Heartwood, from The Lost Words, Spell Songs.

Today, I walked under changeful northern skies to see something that isn’t there. When I asked somebody the way to Sycamore Gap, they replied, “Do you mean Syca - no-more Gap?” - the correction itself carrying the weight of recent history.

For those who don’t know, Sycamore Gap sits along the escarpment that carries Hadrian’s Wall - and in the dip between its rolling shoulders stood a single sycamore tree that became one of the most photographed and visited spots in the country. In September 2023, that tree was cut down overnight in an act of vandalism that shocked the nation.

Within a wall built as an assertion of dominion and control, a sycamore seed found soil in the crease of the land and rose beside the line of stone, right at the heart of the dip. It was never the oldest tree, nor the rarest, nor botanically extraordinary - but what it became was something else entirely.

The shock that travelled across the country when the tree was felled told us something. The reaction was not simply about timber. It was about a rupture in something shared.

It was the notions we attached to that dynamic that were brought so sharply into perspective. For before that - its meaning was something that hid beneath the reality of our everyday existence - we were just drawn to the idea of it, the visual beauty of it - but didn’t quite know why.

As with most things that we suddenly lose, the presence of absence shapes the thing that is absent more acutely for us. It clarifies the ambiguities, articulates the vapour, the vague feelings that flow deeply within us.

We do not always know why certain things speak to us, but they do silent work on our behalf. They hold our values in visual form.

And, in the aftershock of loss - the lens sharply focused on the why, what and how of it all - I realised that the Sycamore Gap was never just about a tree. It was more about a composition.

The gap mattered as much as the sycamore. We were drawn to the symmetry of it - the horizontal line of empire, the vertical line of life. The tree spoke of the natural order of things, of a candle in the dark, of David and Goliath - it awoke the humanity in us: resilience without spectacle and the capacity to occupy a space without needing to control it. It also spoke of the human ability to recognise balance and to honour the peace of wild things.

Perhaps that is why its destruction felt so jarring in an age already thick with domination, asymmetry, misinformation and certainty. Its loss amplified the lack of agency and control that we feel. It was an assault not simply on the tree, but on a shared metaphor. When we lose contact with nature - when we rise too far above ourselves and believe we control the narrative entirely - something vital erodes.

But the story is not over - for like an eternal well, the human spirit keeps searching for hope and meaning - and that search has now been re-centred upon the stump itself. For within the harshest of environments, after succumbing to the basest of human intent, new shoots are growing.

And that means the world to me - because in a time when the horizontal lines of power can feel overwhelming, the vertical line of life is rising again in the very gap that first taught us how to see it.

Memberships are a real lifeline - can you help keep me on the road? Thank You 🤗

Lots of Member Benefits

Support The Digest

If you know of people, publications or organisations that align with this way of moving through the world — pilgrimage, landscape, history, recovery, slow travel — I’d be glad if you mentioned this journey to them, or shared this post with them on social media.

It really does help keep me on the road. Thank you.

Please feel free to download the video to share, or download any of the photos on this post by right clicking and choosing download.

Here is a link to a summary of my journey In Pursuit of Spring:

THE JOURNEY SO FAR 🚐 ❄️ ⛰️ 🏛️ 🌨️ 🌊

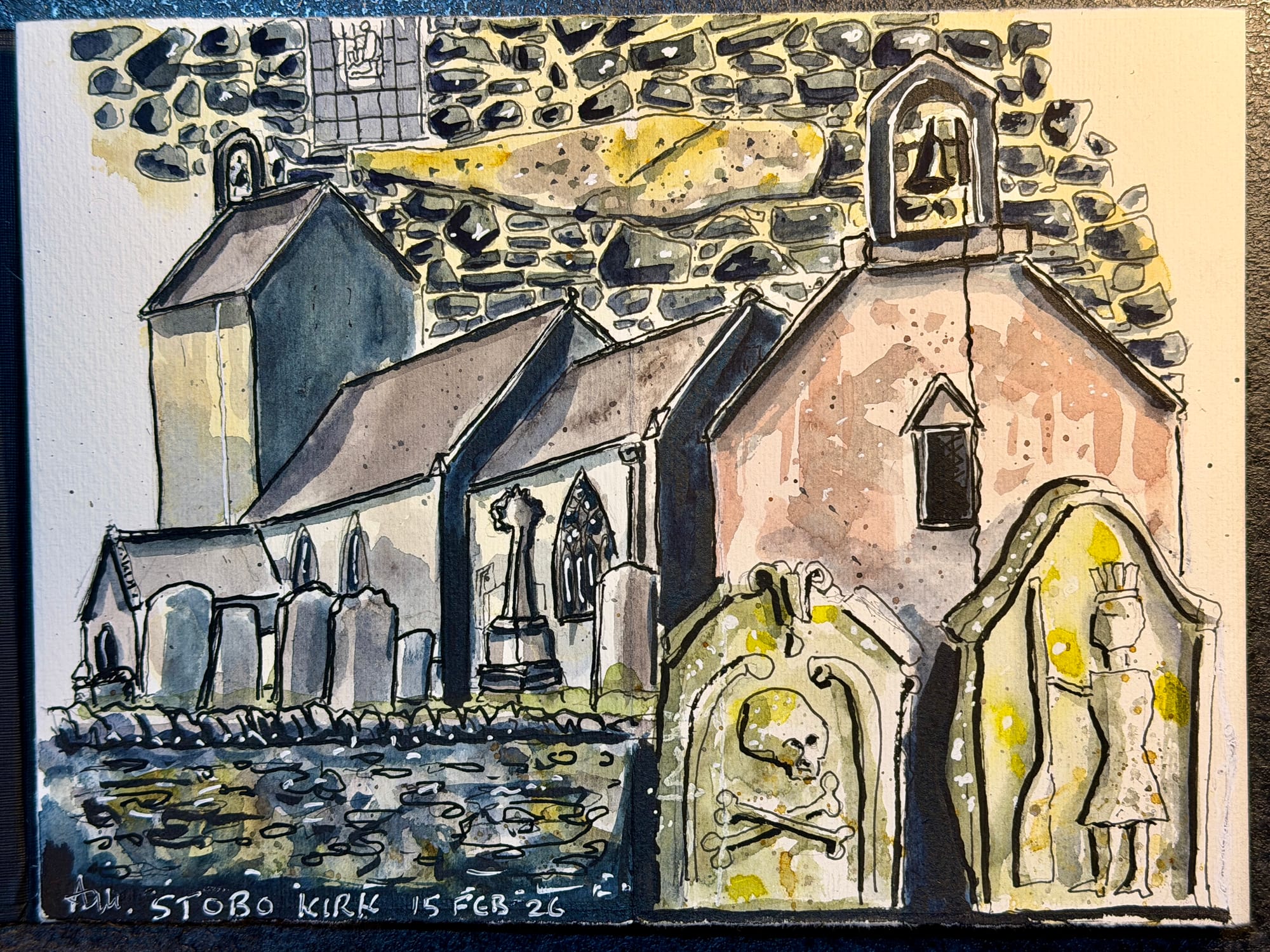

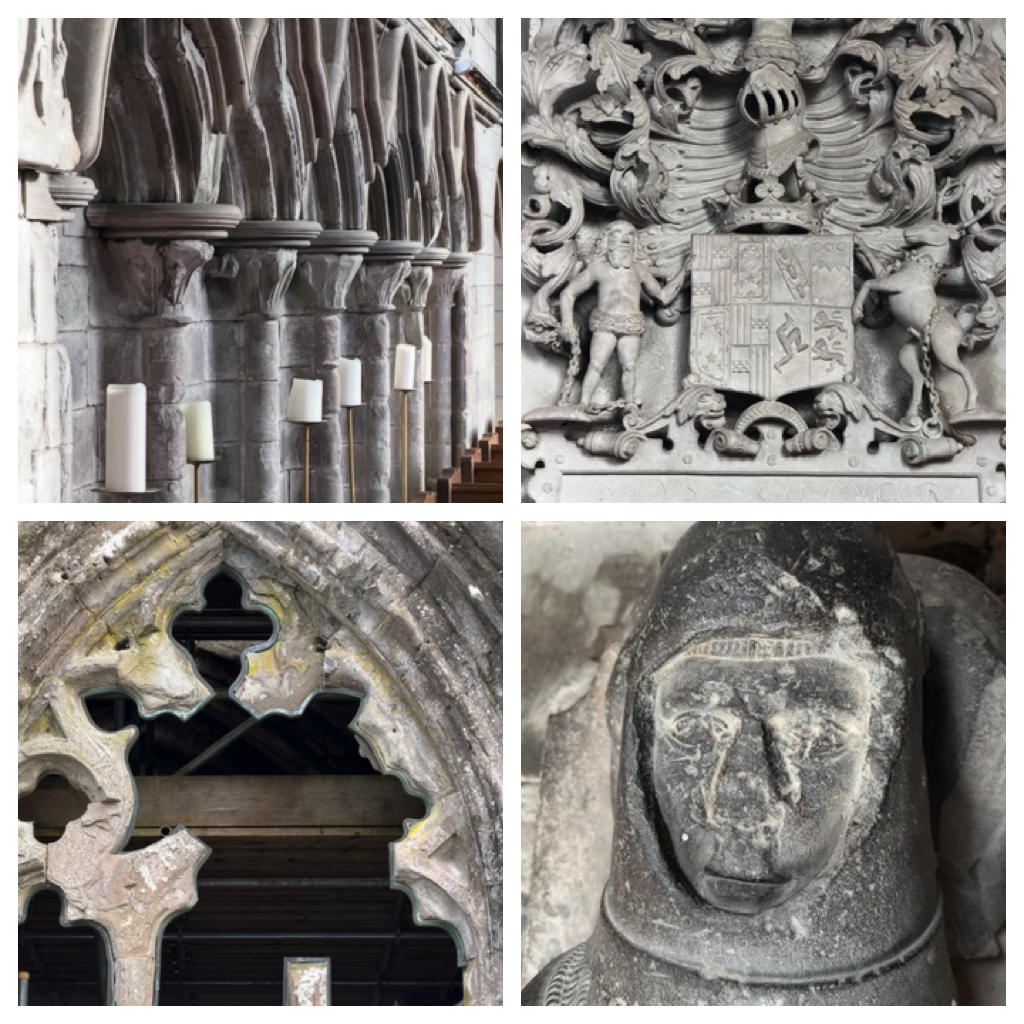

Stobo Kirk

Stobo Kirk is one of the oldest churches in the Borders - once the principal church of the Upper Tweed Valley in medieval times. It is said that St Kentigern - St Mungo - converted Merlin here.

My first sight of Stobo brings relief. The journey along the A72 had been hard going - blizzard conditions tearing across the Borders landscape, the van nudged by crosswinds.

When I arrive at the church, Sunday service is about to begin. In the porch I am greeted by a smartly dressed gentleman in a tweed jacket. Have you travelled far? he asks. From Bury - north of Manchester. His face lights. I worked down there in textiles. I glance at his jacket - its weave, its pattern - and think about the strange pattern of connection and how threads cross. I think about how strangers recognise one another through geography, through craft and shared ground.

Through his words he reaches back to my home and draws a root from it and ties it into this place. His welcome feels like an embrace.

The church is an embrace too.

It has been holding this valley for centuries - and before that, something else held it. The Norman fabric enfolds ancient stones. One of them - set into the wall - looks like a whale: a creature from deep time surfacing into the stony present. Later, as I sketch it, a word begins to surface, one that rises above all the incremental shifts of belief this place has known.

Sacred.

It’s a word that isn’t confined to doctrine - but is more about the way we value things. It’s an instinct that feels inherent - to mark certain places, certain stones, certain gestures, as set apart. It may be the cosmos, a standing stone, a tree or a child’s smile - or the simple grace of a man in a porch who chooses to connect.

Inside the north transept - now a Christian altar - rests a pagan stone reputedly brought here by Mungo himself - its meaning changed but the sacred has remained intact, threaded through from pagan to Christian.

Stobo does not feel like a site of replacement - one faith laid over another. It feels cumulative. As if each age has added its own layer of reverence without entirely silencing what came before. The sacred here is not fragile - it is sedimentary, held, quite literally, within the walls.

On my first day, in pursuit of spring, I have found a stone carried forward, a pattern recognised, a welcome received and the warmth of humanity within a blizzard - and with it, a sense of the sacred threaded through humanity itself.

Loch an Eilein

There was a moment at Loch an Eilein - only the briefest of moments - but it was a moment where time stood still, where the earth and sky and light and shade were as one. Just before it happened, I’d taken up my sketchbook and used water from the loch to fix my paint.

It was at that instant that the sharp easterly dropped and beyond the forest of Rothiemurchus, the snow bones of Creag Dhubh tousled the clouds into thin wisps of galloping guilloche.

Had I stumbled upon an ancient spell?

Mix a phial of loch water with a squirrel brush and Roman Szmal half pans, say ‘Rothiemurchus’ three times, paint the scene before you - and, hey presto - time starts to stand still - the castle on the island in the middle of the loch - becomes a thin place.

It’s happened before at other locations within these isles, but this time I was ready for it. Far too often moments like this have come along and the veil of modernity has turned my eye - but not this time.

I stood on the jagged shoreline, put my sketchbook and paintbrush down and watched the loch clear of all its angst and its worry and offer up a mirror into another world.

And then, as quickly as it came, it was gone - the branches above me began to creak again, the jackdaws rose from the tumbling parapet, and the loch folded the other world back into itself.

The paint still wet upon the paper held what the water had briefly revealed - a stillness carried forward upon the page.

I can’t tell you how magical it feels to visit Portmahomack on a cold, crisp day with the raking winter sun pricking out the harbour and the buildings that embrace it.

The village sits on the west-facing coast of the Tarbat Peninsula, looking out across the Dornoch Firth towards the Moray coast. It feels both exposed and sheltered all at once - between the Highlands and a sea inhabited by dolphins and seals.

The seals gather along the shore and sandbanks - dark heads bobbing and slipping beneath the surface with hardly a ripple. In this light they almost look human. It is easy to understand how selkie stories took root here - creatures moving between elements, shedding one skin for another, inhabiting parallel worlds of land and sea.

My arrival felt like an initiation into a parallel world.

Woken in the night by the cold and the dark skies of Grantown-on-Spey, I drove north through winding B-roads beyond Inverness, crossing firth after firth on low bridges into the Black Isle and over the Cromarty Firth. It felt like moving through narrowing bands of geography.

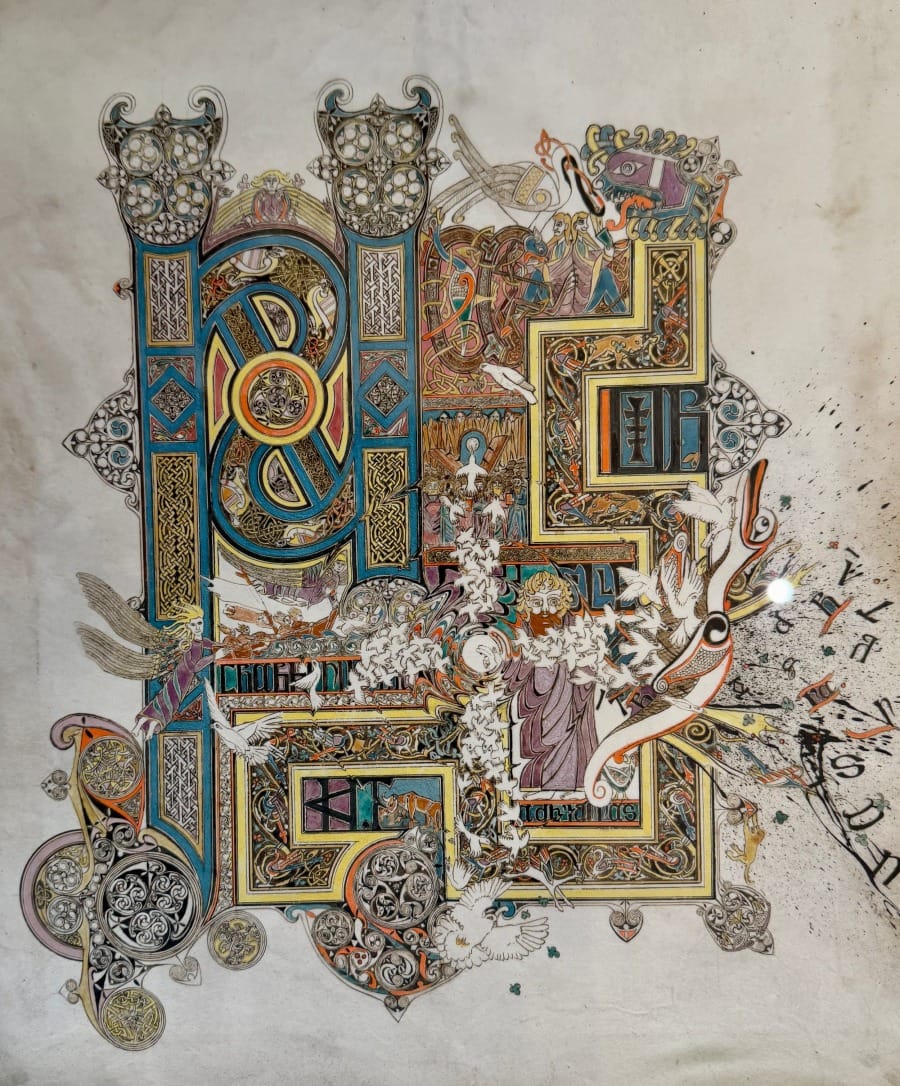

Portmahomack was the site of one of the most significant early medieval monastic settlements in northern Britain. The Tarbat Discovery Centre - housed in the restored medieval church of St Colman - contains within its lower fabric remnants of the earlier monastery. Excavations directed by archaeologist Martin Carver revealed an 8th-century Pictish monastic complex of remarkable scale and sophistication.

Among the finds were fragments of finely carved Pictish cross-slabs - some shattered, many bearing intricate interlace, beasts and scriptural imagery. Archaeologists also identified a distinct burnt layer dating to the late 8th or early 9th century - widely interpreted as evidence of a Viking raid. It is considered the earliest clear archaeological evidence of a Viking attack on a monastery in Britain.

There were also earlier discoveries in the wider region - enigmatic Neolithic carved stone balls, found across northeast Scotland. Their purpose remains unknown. They sit in the imagination like coded objects from a civilisation that has withheld its key.

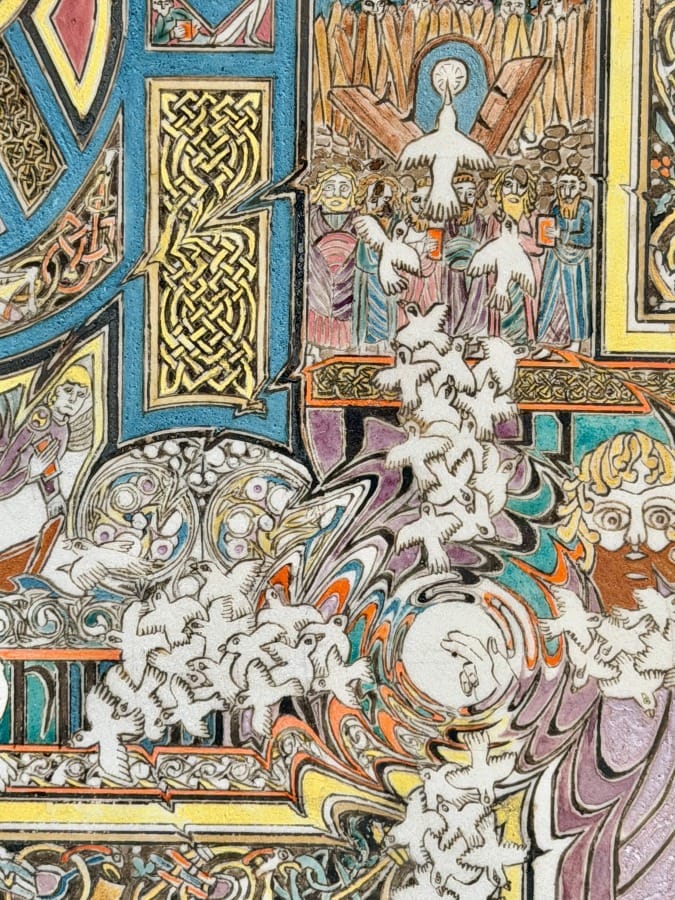

What becomes clear at Portmahomack is that this monastery was not peripheral. It was literate, organised and deeply connected. Evidence suggests specialist workshops here - including vellum production from calf hide, metalworking and manuscript preparation. Some scholars have proposed links between the monastery’s craft traditions and the wider Insular world of book production - the same artistic milieu that produced the Book of Kells. While it cannot be proven that vellum for Kells was made here, the geometric interlace and animal forms carved in Tarbat stone belong unmistakably to the same visual language.

This was part of what we call Insular Christianity - a strand of early medieval Christian practice that developed across Ireland, Scotland and Northumbria. It was not a separate religion from Rome, but it expressed itself with distinct artistic, liturgical and monastic characteristics before eventual alignment with Roman practice in later centuries.

In the centre, a contemporary artist has created illuminated scripts in the Insular style. To stand before one is to realise that an illuminated manuscript is not simply decoration around text. It is a singular world compressed into a page.

To enter it, I have to drop everything I know about reading. I have to unlearn the left-to-right logic of narrative. I have to loosen the grip of beginning, middle and end.

I take heed from the seals around these parts, and the Selkie Boy Song on my playlist:

Oh selkie-boy, swim from the shore,

Rinse your ears of human chatter

And empty your bones of heather and moor,

And your mind of human matter

Once my mind quietens, the page is unlocked.

An illuminated manuscript is both portal and labyrinth - a super-concentrated cosmology contained within animal forms, spirals, knots and sacred text. The interlace has no clear beginning and no termination. You enter anywhere. Your eye follows a curve, crosses a border, returns through pattern into image, and image into letter. Each viewer’s route differs - but the theological and symbolic universe remains constant.

Standing there in Portmahomack with the wind scudding off the firth, I realised that this small peninsula generated so many parallel worlds.

Not just stone and pigment, but entire cosmologies. In a place that feels at the edge of the map, monks were preparing calfskin, grinding pigments and bending geometry into devotion. The Vikings burned it and then the sand covered it. Yet the language of those pages - circular, non-linear, inexhaustible - still survives.

It’s a lesson unto ourselves, in an age where we think we have the answers - that there are alternative ways of seeing that might provide alternative ways of solving.

Portmahomack is not a ruin of the past. It is proof that even at the margins, the imagination of a people can be vast - and that a single page, properly attended to, can hold an entire universe.

Dunkeld Cathedral sits beside the River Tay in one of the most bucolic locations I have come across - even on a stark winter’s day. What survives of the building has seen over a thousand years of change - saints have come and gone, renovations, collapses, reformations, shifts in liturgical order - and yet it still stands next to the muscular calm of the river marking time with its ebb and flow.

I find myself looking up at the rising west end and thinking about the time it must have taken to build this place - the cusping, the shaped hood moulds, the grotesques, the stiff leaf carving, the blind arcading.

“Build me a cathedral!,” somebody must have said - and then all the human resources, finance, stone, timber, skill and faith came together to create something so seemingly impossible. Generation after generation contributing to a vision none of them would see completed. The moral imagination of a society made visible in stone.

Not more than a mile away from such intricacy stands another rarity - this one less architectural, but no less monumental. The Birnam Oak stretches out towards the Tay - a vast, hollowed bowl of timber, its trunk split and contorted, its limbs propped and sprawling, bark thick as armour. It feels less like a tree and more like a living remnant of another age.

It was Birnam that became the turning point in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. After his violent ascent to kingship, Macbeth is told he will remain safe until Birnam Wood comes to Dunsinane - a prophecy that appears impossible. Forests do not march. Trees do not uproot themselves. And yet the impossible happens - his opponents cut branches from Birnam Wood and carry them as camouflage towards Dunsinane Hill. The forest appears to move. The prophecy is fulfilled. The moral imbalance created by Macbeth’s unnatural force corrects itself.

This oak was a sapling when Shakespeare wrote those lines.

Macbeth achieves his crown through violence against the moral order of his world. What the oak represents for me is the inevitable reassertion of that order.

I walk around the tree in awe at its size, but my eye is drawn to something smaller - an acorn resting in the leaf mould. How mighty is this thing that fits within the palm of my hand? Those who can carve hood moulds and cusping, those who can mobilise labour across generations to build a cathedral - none of them can build this. Not one of them can summon up the knowledge that turns seed into living fibre, timber into filigree forms. Only an oak tree can do this.

Both cathedral and tree are parallel testimonies. The cathedral reveals what human beings can achieve when they organise themselves across generations. The oak reveals a deeper order - one that regenerates itself without committee or finance or proclamation, through the moral architecture of nature itself - and, in a shapeshifting age that Macbeth might recognise, there’s something deeply comforting about that.

Coming soon for Members - video, virtual reality, aerial shots extra posts and behind the scenes content from this epic journey

Kind words from a subscriber:

Andy your work is becoming wonderful, remarkable. A so-called breakdown has been milled into its constituent parts, becoming profound construction: through perception, architecture, the lens and the pen. In your Repton crypt essay a deep description of our social anxiety - and our reason to be....

Recent Digest Sponsors:

Thank You!

Photographs and words by Andy Marshall (unless otherwise stated). Most photographs are taken with iPhone 17 Pro and DJI Mini 5 Pro.

🔗 Connect with me on: Bluesky / Instagram / Facebook / X / Tumblr / Flickr / Vimeo / Pixelfed / Pinterest / Flipboard/ Fediverse: @fotofacade@digest.andymarshall.co

Member discussion