In Pursuit of Spring

I can’t tell you how magical it feels to visit Portmahomack on a cold, crisp day with the raking winter sun pricking out the harbour and the buildings that embrace it.

The village sits on the west-facing coast of the Tarbat Peninsula, looking out across the Dornoch Firth towards the Moray coast. It feels both exposed and sheltered all at once - between the Highlands and a sea inhabited by dolphins and seals.

The seals gather along the shore and sandbanks - dark heads bobbing and slipping beneath the surface with hardly a ripple. In this light they almost look human. It is easy to understand how selkie stories took root here - creatures moving between elements, shedding one skin for another, inhabiting parallel worlds of land and sea.

My arrival felt like an initiation into a parallel world.

Woken in the night by the cold and the dark skies of Grantown-on-Spey, I drove north through winding B-roads beyond Inverness, crossing firth after firth on low bridges into the Black Isle and over the Cromarty Firth. It felt like moving through narrowing bands of geography.

Portmahomack was the site of one of the most significant early medieval monastic settlements in northern Britain. The Tarbat Discovery Centre - housed in the restored medieval church of St Colman - contains within its lower fabric remnants of the earlier monastery. Excavations directed by archaeologist Martin Carver revealed an 8th-century Pictish monastic complex of remarkable scale and sophistication.

Among the finds were fragments of finely carved Pictish cross-slabs - some shattered, many bearing intricate interlace, beasts and scriptural imagery. Archaeologists also identified a distinct burnt layer dating to the late 8th or early 9th century - widely interpreted as evidence of a Viking raid. It is considered the earliest clear archaeological evidence of a Viking attack on a monastery in Britain.

There were also earlier discoveries in the wider region - enigmatic Neolithic carved stone balls, found across northeast Scotland. Their purpose remains unknown. They sit in the imagination like coded objects from a civilisation that has withheld its key.

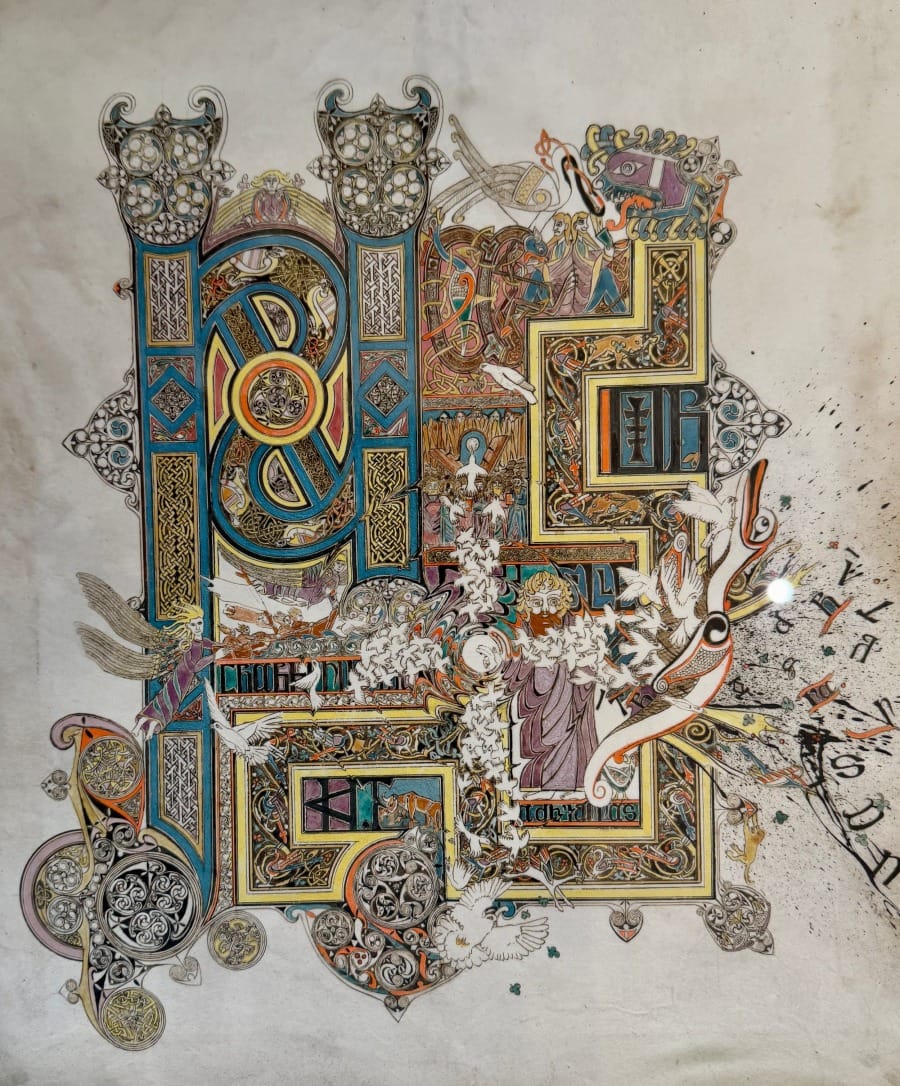

What becomes clear at Portmahomack is that this monastery was not peripheral. It was literate, organised and deeply connected. Evidence suggests specialist workshops here - including vellum production from calf hide, metalworking and manuscript preparation. Some scholars have proposed links between the monastery’s craft traditions and the wider Insular world of book production - the same artistic milieu that produced the Book of Kells. While it cannot be proven that vellum for Kells was made here, the geometric interlace and animal forms carved in Tarbat stone belong unmistakably to the same visual language.

This was part of what we call Insular Christianity - a strand of early medieval Christian practice that developed across Ireland, Scotland and Northumbria. It was not a separate religion from Rome, but it expressed itself with distinct artistic, liturgical and monastic characteristics before eventual alignment with Roman practice in later centuries.

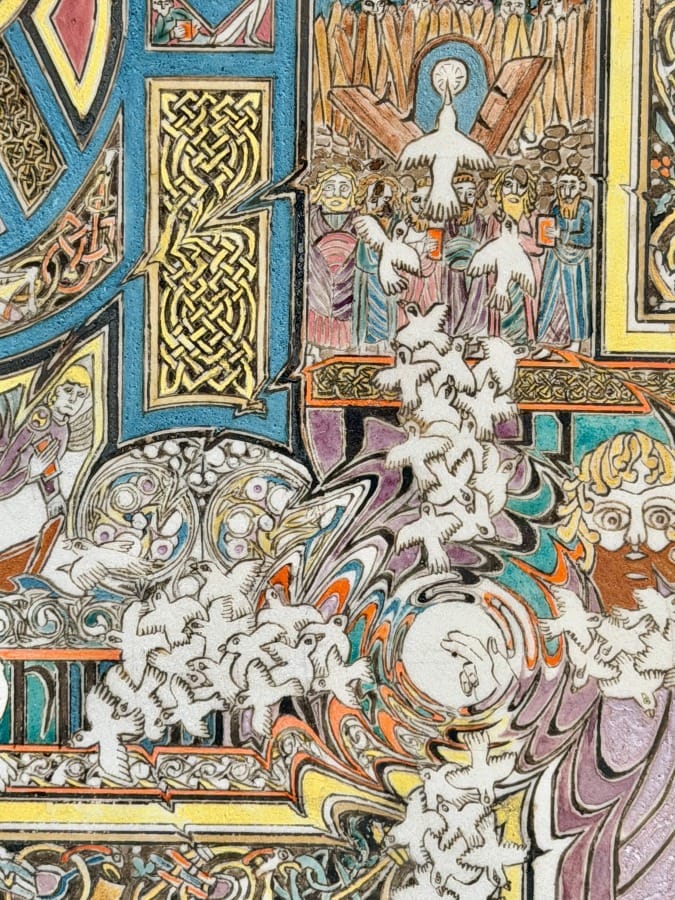

In the centre, a contemporary artist has created illuminated scripts in the Insular style. To stand before one is to realise that an illuminated manuscript is not simply decoration around text. It is a singular world compressed into a page.

To enter it, I have to drop everything I know about reading. I have to unlearn the left-to-right logic of narrative. I have to loosen the grip of beginning, middle and end.

I take heed from the seals around these parts, and the Selkie Boy Song on my playlist:

Oh selkie-boy, swim from the shore,

Rinse your ears of human chatter

And empty your bones of heather and moor,

And your mind of human matter

Once my mind quietens, the page is unlocked.

An illuminated manuscript is both portal and labyrinth - a super-concentrated cosmology contained within animal forms, spirals, knots and sacred text. The interlace has no clear beginning and no termination. You enter anywhere. Your eye follows a curve, crosses a border, returns through pattern into image, and image into letter. Each viewer’s route differs - but the theological and symbolic universe remains constant.

Standing there in Portmahomack with the wind scudding off the firth, I realised that this small peninsula generated so many parallel worlds.

Not just stone and pigment, but entire cosmologies. In a place that feels at the edge of the map, monks were preparing calfskin, grinding pigments and bending geometry into devotion. The Vikings burned it and then the sand covered it. Yet the language of those pages - circular, non-linear, inexhaustible - still survives.

It’s a lesson unto ourselves, in an age where we think we have the answers - that there are alternative ways of seeing that might provide alternative ways of solving.

Portmahomack is not a ruin of the past. It is proof that even at the margins, the imagination of a people can be vast - and that a single page, properly attended to, can hold an entire universe.

Weather: -8 degrees celsius morning - 5 degrees celsius daytime.

Observations: Cormorant on seashore. Did I hear a cuckoo? Surely not?

Total Miles Travelled: 525

"That aura, those echoes-the muted light is transporting. What a space to feel rooted in history. I'd love to make that journey myself; you've stirred the opera lover and architectural dreamer in me."

@sonatasips via X

"In reading & seeing Andy's work I always struggle to know which is more impactful - his writing or photos. In truth, the two combined are greater than their parts, he allows you to explore the importance of place and time from the comfort of home."

Peter from Bluesky

This work is sustained by a small group of tier members who value time, care, and continuity. If that resonates, there’s a more immersive path you can step onto. Become a Tier Member:

Connect with me on:

Bluesky / Instagram /Facebook /X / Tumblr / Flickr / Vimeo / Pixelfed / Pinterest

Member discussion