I visited the historic Saxon tower at Bosham recently. It was covered in what I would call render or rough cast and, I have to admit, I would normally feel a little tension at not being able to see the stone beneath. But, perhaps without the outer coating the tower wouldn't be standing here at all - with the salty gales ripping across the English Channel. Thankfully - I was better informed on this trip - after speaking to Dr. Tim Meek (a subscriber and member of this digest) about his work with lime mortars.

The tower at Bosham has an appealing co-mixture of render and stone - that seems to work like sinew and muscle - a kind of synergous relationship. Tim tells me that the quoins would also have been plastered because they have been stugged and broached to accept plaster. Details like this are invaluable at working out the story behind a building.

After lauding over brick and stone on Twitter, Tim offered to write a piece on the beauty and necessity of coated buildings.

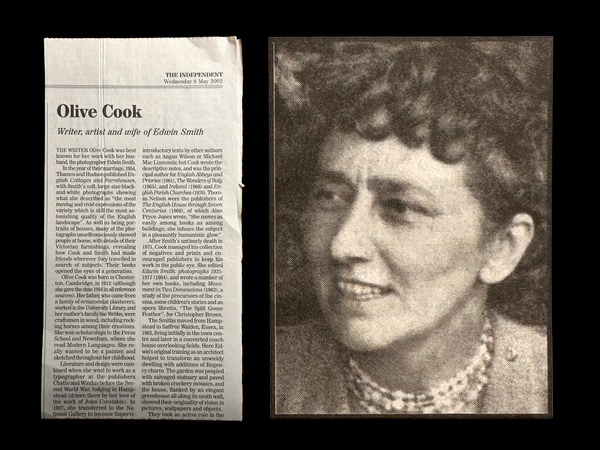

Dr. Tim Meek

You and I see our built heritage differently. You see buildings with time and age value, with the colours and textures of decay, what Ruskin called the golden stain of time and that the true colours of architecture are those of natural stone. As builder, then archaeologist and more recently heritage scientist, I examine the evidence of how buildings were presented in the past and how they functioned.

What the evidence tells us is that pre-industrial architecture was coated. The coatings were varied and might evolve over time, generally lime based, often colourful and invariably, rubble was covered, what William Adam called Rough work or masonry well executed but understood to be coated. In the example where he uses this term, Mavisbank in East Lothian, he is describing two rubble-built sweeping walls which he tells us the masons will harl once the building work is complete.

Harl or roughcast being a coarse blend of sand, lime and aggregates: the process a deft flick of the wrist from a small trowel to provide an opaque and textured surface to masonry. But lime coatings might also be flat plaster and there is compelling evidence that many plasters were lined out to mimic what we now call ashlar. This is exactly what Adam did at Floors Castle.

The presentation of buildings is then crucial because it fulfils two roles: it displays to the world an outwardly sense of place and an understanding of the role of taste and politeness in society. In appreciating this it also demonstrates an innate sense of how buildings work, a relationship then between the seemly and seamlessness. I argue that Britain has lost this cultivated sense of a practical aesthetic. When you see bare rubble, I see decay. When you see recessed pointed joints, I see water penetration, a position made prescient in a climate changed future, raising questions relative to what conservation is and who it is for.

The beauty of lime finishes is that they are regenerative, constantly renewable, the multi-layering providing newness value, a term I have adopted to describe immaterial values of the many of bricklayers, masons and plasterers who have remained silent over the past thousand years. We admire our work as we clean down our tools at the end of the day. We understand what our achievements says about our skill and how it fulfils the ambitions of those who commissioned such work, and we know that with periodic patching and maintenance we don’t have to accept that our buildings will fade. The world of conservation has become the problem not the solution and has ascribed a vulgarity to the language of architecture that was not our intent.

My mission and those of a small but growing body of trades, architects, scientists, conservation officers and academics is to change the narrative, to make sense of the past and demonstrate that Britain wasn’t simply a rustic idyl and in doing so we have a chance to secure our old buildings.

About Dr Tim Meek.

Tim served an apprenticeship as a bricklayer and in his early twenties went to night school and took ‘O’ and ‘A’ levels. In his late twenties studied Archaeology at Newcastle University and later a Masters in Conservation Studies at York. In between studying he had his own business applying lime finishes at home and abroad. He has taught at the Prince of Wales School of Architecture and has recently completed a PhD examining the cultural and physical factors of lime finishes in Scotland.

Tim is on Twitter

Have your say.

This is a fascinating topic. Please comment below if you want to join in on the conversation.

Are you a member or subscriber and would like to provide an insight into your field of expertise that relates to our built environment? Drop me a line with your details.

Member discussion