Welcome!

⚡️ View the latest digest and the full archive here.

📐 My Goals ℹ️ Donations Page & Status 📸 MPP Status 🛍️Shop

(°v°) Photo-hoard

Up where the crows fly: the parapet minstrels of Selby Abbey

The Crow

With rakish eye and plenished crop,

Oblivious of the farmer’s gun,

Upon the naked ash-tree top

The Crow sits basking in the sun.

An old ungodly rogue, I wot!

For, perched in black against the blue,

His feathers, torn with beak and shot,

Let woeful glints of April through.

The year’s new grass, and, golden-eyed,

The daisies sparkle underneath,

And chestnut-trees on either side

Have opened every ruddy sheath.

But doubtful still of frost and snow,

The ash alone stands stark and bare,

And on its topmost twig the Crow

Takes the glad morning’s sun and air.

William Canton

(°v°) Observations

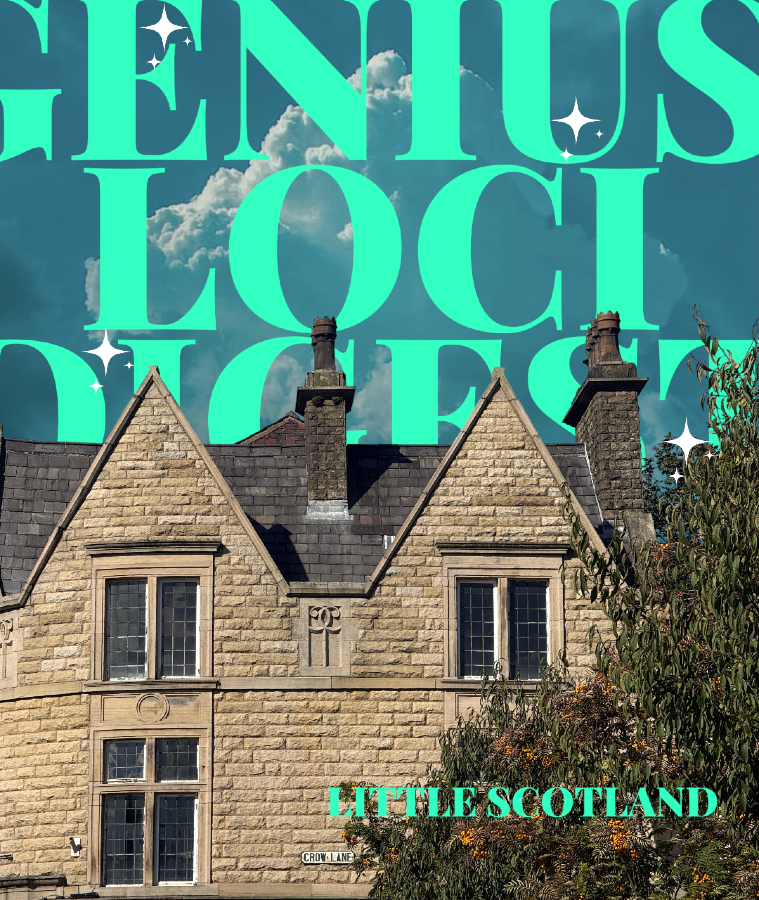

Ramsbottom.

Your poets saw darkness here, and nothing more, but in the cerulean sky we are mirrors catching the sun. We are mirrors that are black then white like flecks of polished jet, mirrors that shape-shift and dance to our own song, mirrors that are so constant and timeless that we have given those that dare to see the glint in our blackness a great gift: the power to see themselves as we see them.

We saw humans arrive one evening as the sun swung low over snow-capped hills that they would call Whittle and Whitelow. Whilst the great glaciers retreated and Cheesden echoed with the sound of savage water and the Irwell began to cut its way through the upper valley, we bounced the light off a world in flux.

You didn’t know it and many still don’t — that we counted and named each hill and indentation where you dwelt — names that we croak in as many tones and timbres as the forest chroma beneath us.

You called us all one name. You called us crow.

We saw the valley turn green — the marsh retreat, the elder and the ash grow strong. We watched the wolf and the bear hunt in the glade whilst you rutted tracks from the hillside and buried your dead in urns. It seems you were all about circles then — the ebb and flow into the hills, the pots and cairns, the gatherings around a blaze.

We saw the last wolf and bear replaced by the great stockade where herds of deer, amidst your hollering throng, cantered into a single tilt — barking, scattering through the bluff, caught in confusion, and falling within the bloody bounds of Musbury.

Whilst hovering over Watling and sat on the Pilgrim's cross we caught your prayers to Winefrede and Cuthbert.

And then divine intervention: they helped you clear the trees in the valley.

And after the clearing came the farm and the house — the first puff of smoke from the gabled chimney; its buff stone roof taken from a hole in the ground at a place you called Haslingden. Your nest was all about keeping the weather out — hood-moulds over the doors and windows, walls set in watershot like our preen-oiled coats.

And then you planted more trees — kept within the bounds of a wall with cocked hat copings — all ordered in a pattern that garnered fruit that intoxicated us, drew us in to the last ash and elder next to your gable. Here we settled and watched the rut into the valley become a hollow lane and broaden out to the ford beyond Stubbins.

Your sedentary gait turned into a hurried trait as you peeled back the river. We saw it dammed and sluiced. You exchanged your living circles for straight lines that linked the river to mills and the road to towns. You built a bridge that saw the last toll for the old lane.

And then one day whilst slugging worms from the soft clay at Whitelow we heard the thud of cattle hooves and saw a family of drovers pause and look into the valley at the farmhouse and the mill with the waterwheel. They’d come from beyond Cuthbert. They spoke with a strange lilt. Corbies they called us.

The Corbie folk returned without their cattle and, as fast as the clouds skid over Holcombe, the landscape changed beneath. They parcelled up the valley sides with hedge and wall. Then came a building as big as ten houses. It was here that we saw our second puff of smoke and then it multiplied and soon the smoke was as thick as the fog that hung in the Cheshire plain.

Not all the buildings had smoke, some nested workers, some fortified them, others rang bells out loud. But one thing many had in common were the high gables and odd tilts — the Corbie folk's accent in stone and slate.

And we heard this place called “Little Scotland” and the packhorse route that linked you to Cheesden, Scotland Lane.

Then it happened — our roost no more, our trees gone. The farmhouse stripped clean of its hood moulds and stone — the orchard hacked down and the cocked hat copings to the garden wall replaced by huge stacks of ashlar.

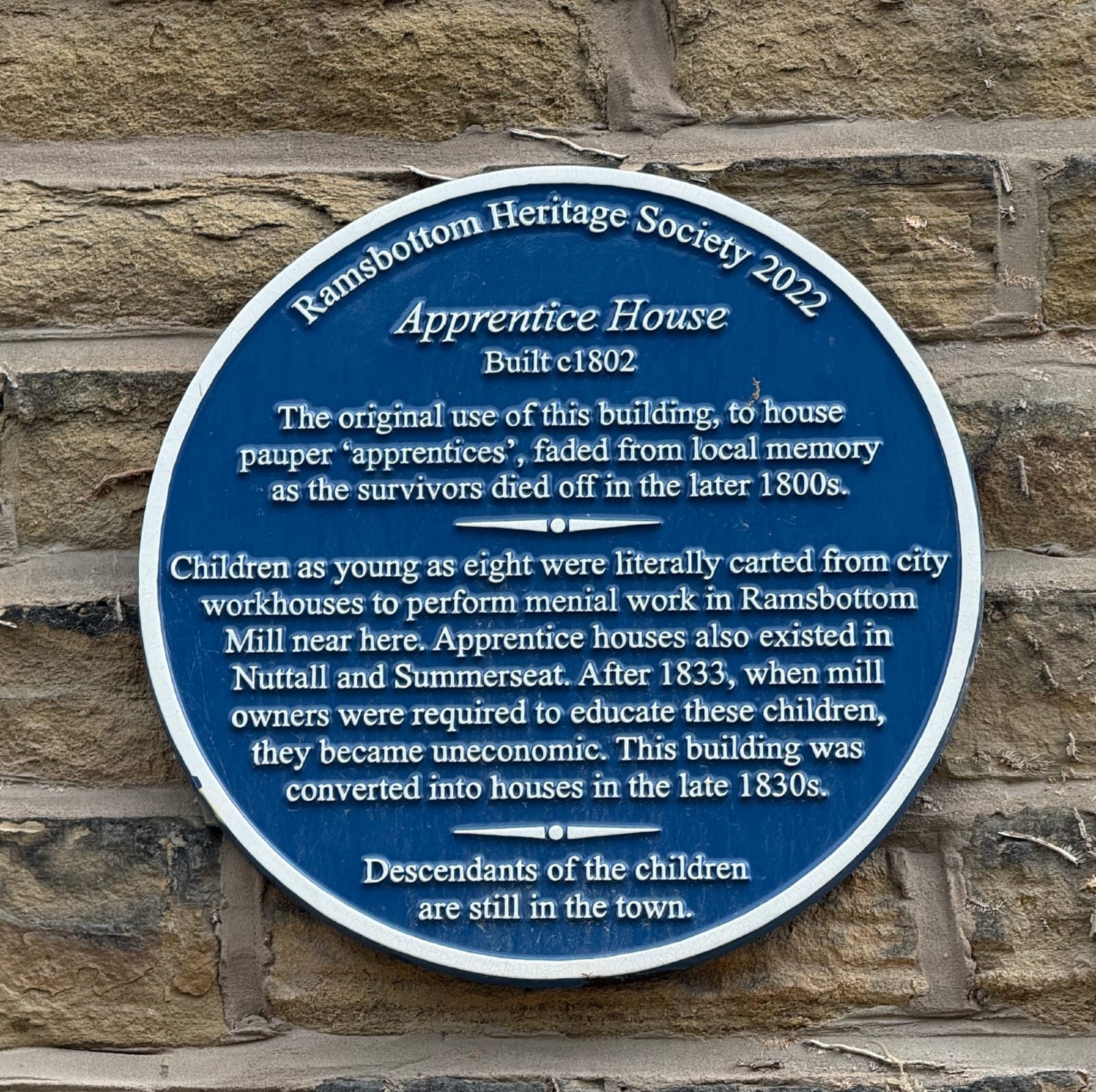

Homeless, we struck out into a remnant copse and watched the old farm hood mould and copings fixed to a new house on the ancient lane that they stoppered with a mill and damp hovel that held a motherless offspring of apprentices. Odd it was for us to see the great ashlar building, crowned with a spire, draw the godly to it, and then, on other days, watch the revenant mites from the apprentice house cast into the smokestacks.

And then Clayton came to tend the horses and the machines. When we first saw him crouch through the door after a hard day’s bind — eyes blinking from the sharp light, his face as black as coal — we cackled uncontrollably, for he was the first of you to look like us.

Not long after, we heard the clunking and chinking of metal and soon the toot of a whistle until, one morning, you gathered around its base and hailed its arrival through great bronze horns and crimson flags.

The great tooting, fire-breathing beast brought in order. In its body it held brick and slate and soon the vast honeycomb of buff stone roofs on the old town was replaced with a blue-grey that dazzled us with its sheen, glinting up the hillside on rainy days.

You hailed in the street lights and the sewers, the clock and the nine-to-five; conformity and non-conformity, order and progress — and then wept as the beast took your sons to war. On sunny days we tell the time by the memorial you built to them — our gnomon — its shadow facing west in the morning and east in the afternoon.

Over time the pace changed: walking, then cantering, then something else — people enclosed in bubbles, moving swiftly through the streets as if there were no time to stop.

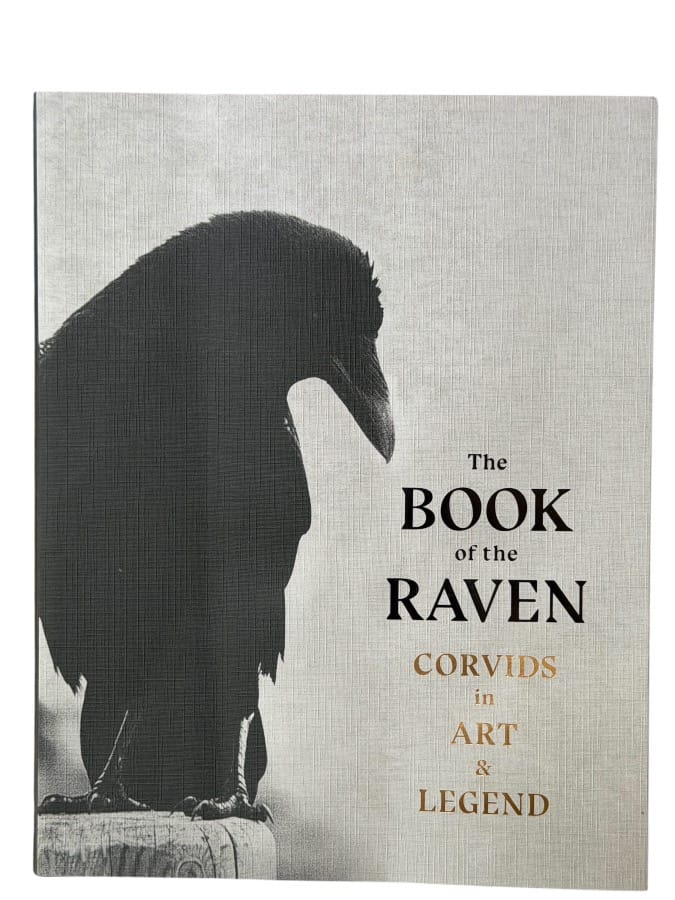

One day, whilst riding the thermals above the moor, we glimpsed our likeness, along the pilgrim road, in a book you called a bestiary — a book that spoke of our kind as thankless, neglectful, ungrateful.

Then came the forebodings and the prophesying, the Poe’s and the Hughes’, the Tolkien’s and the Hitchcock’s.

You had forgotten that we were the first from the ark.

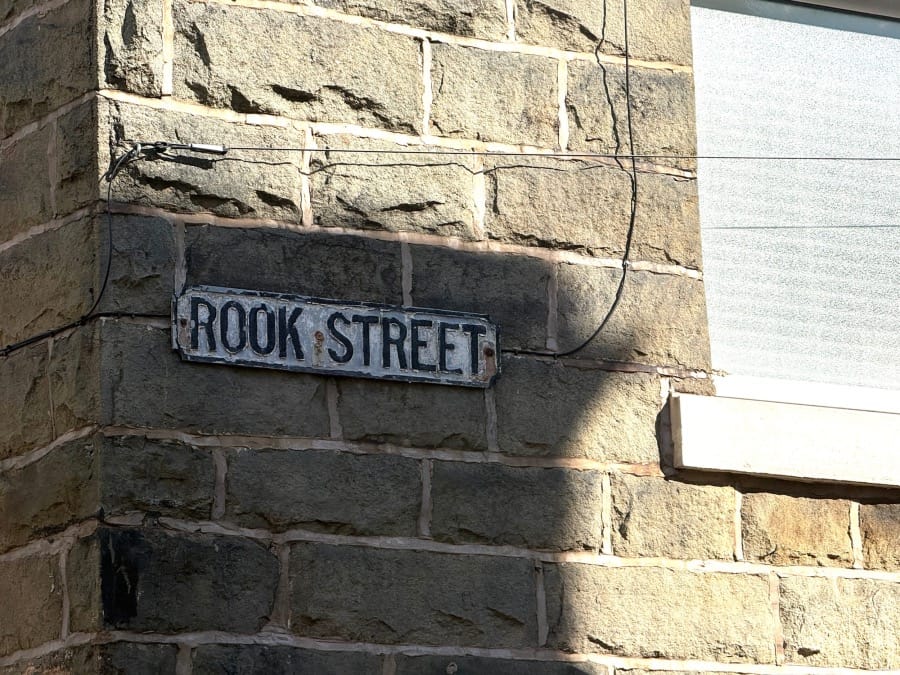

For a while we thought you unkind, yet we saw you try and right your own wrongs, over and over again, as if mending were part of your nature. In the unstoppable onslaught of change, this constant was the thing that softened our beady eyes. You showed yourselves in the names you gave, weaving us into the fabric of your place. Only when we had gone did you christen the old lane after us — as though the things that filled your soul with light could only be honoured once they had slipped into shadow.

You called us all one name. You called us crow.

We are the diamonds in the coal — the watchers, the keepers of memory, your unwilling companions and your constant stewards. We are your continuity. Where stone crumbles and chimneys fall, we remain, carrying the spirit of the valley across the generations.

Your poets saw darkness here, and nothing more, but for millennia in the cerulean sky above Ramsbottom there have been mirrors that catch the sun, and on some days, if you look for a glint in the blackness, those mirrors will return your likeness too.

(°v°) Can you help keep me flying up there with the crows?

Lots of Member Benefits

Support The Digest(°v°) Hotspots

Ramsbottom

If men had wings and bore black feathers, few of them would be clever enough to be crows

Henry Ward Beecher.

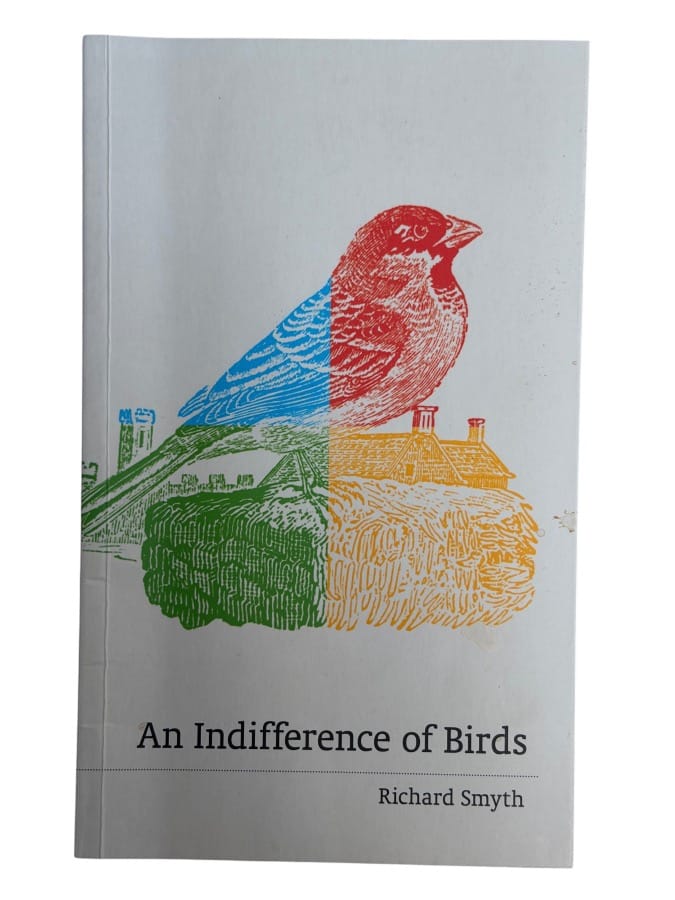

I love Ramsbottom as much as the crows.

I wrote this Digest about the crows of Ramsbottom after researching its history and walking its streets in readiness for a Heritage Open Days Pattern of Streets tour I gave last week. On the tour I shared a different perspective of the town and its buildings — one seen through its material remains.

Here’s more about my tour of Ramsbottom (and Bury) last week:

The Grant Brothers.

The Scottish drovers — the Grant family — passed through Ramsbottom on their way to Manchester. They made their fortune and went on to buy most of the land in Ramsbottom. It is said they thought Ramsbottom reminded them of home in Speyside, Scotland. I wonder if it was because of the rooks?

The Grant brothers were the inspiration behind Charles Dickens’ Cheeryble Brothers in Nicholas Nickleby. Dickens himself kept a pet raven called Grip. When Dickens took Grip to America, Edgar Allan Poe saw the bird — and that encounter is said to have inspired Poe’s famous poem, The Raven.

(°v°) On My Coffee Table

(°v°) And Finally

Your poets saw darkness here, and nothing more, but for millennia in the cerulean sky above Ramsbottom there have been mirrors that catch the sun.

Rooks over the Irwell Valley

Thank You!

Photographs and words by Andy Marshall (unless otherwise stated). Most photographs are taken with Iphone 16 Pro and DJI Mini 5 Pro.

Member discussion