Welcome!

Kind words about the Genius Loci Digest

I just wanted to say thank you for all that you do in producing the Digest. Whenever I spot it has landed in my inbox, I get a thrill of excitement and can't wait to see where you've been and what you've got to tell us this week.

⚡️ View the latest digest and the full archive here.

📐 My Goals ℹ️ Donations Page & Status 📸 MPP Status 🛍️Shop

I think I'd cycle 80 miles in a headwind to see Ely Cathedral. No other cathedral feels so organically grown from the earth itself - it's lantern tower is one of the most verdant wonders of the medieval world.

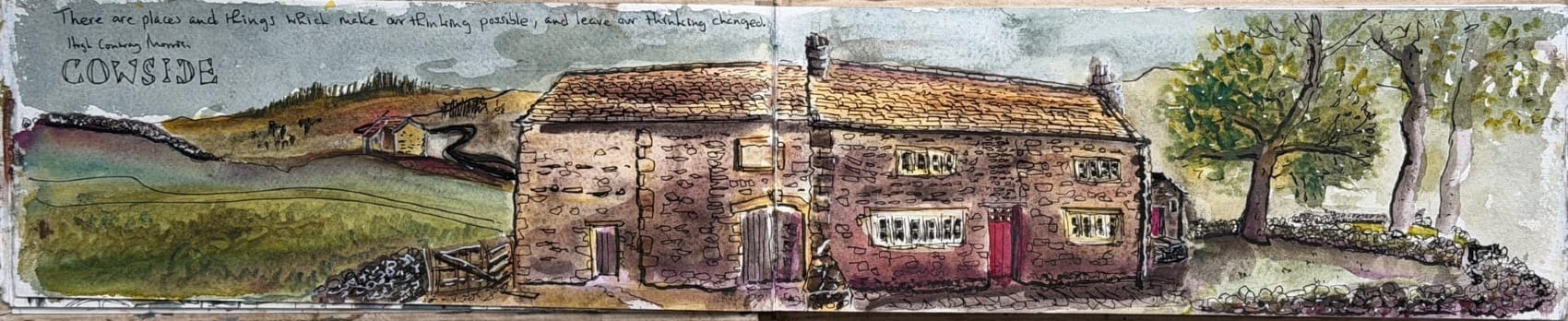

'There are places and things which make our thinking possible, and leave our thinking changed'

Hugh Conway Morris

The Parlour and the Cafe

At first, I found it hard to unwind at Cowside. The ageing walls held a watchfulness that unsettled me. But, gradually, my modern self began to evaporate. I started to idle through its rooms, pausing to take them in before stepping outside to walk its surroundings and observe the dale from the valley side beneath the arcing bow of a curlew’s call.

And then, one evening, sat next to Char, I charged the fire and lit a candle. The walls began to glimmer, and I started to sketch in the golden embrace of the light and became so absorbed that the crackle of the fire startled me. I looked up – the fire had burned to embers, the walls were dancing – and, if I were not a rational person, I might have believed I’d slipped through this thin place into the past, drawn there by some curious potion of time and place, of wick and stove and ink and art.

I think that Stephen Lovatt’s words in Enchanted Ground have something to do with how I felt in that moment:

“One way to reach towards the essence of a time is to accumulate so much material detail that gradually a shape and texture become perceptible through it.”

As I read those words now, they seem to describe not just the way I have come to experience buildings, but how time itself gathers meaning through repetition and return. Perhaps that’s why coming back here after ten years felt so charged.

Visiting Cowside on two separate occasions more than a decade apart offered up a different kind of lens. I remember the first time I visited on commission to photograph it for the Landmark Trust: I worked hard at setting up the best angles for each room and then, during lunch, I stopped and sat amongst the limewash. The silence then, like the walls, had a texture to it, and I remember the joy of being entirely present.

Returning now, ten years later, set up a kind of correspondence between the two versions of myself: one here in the present, digital device in hand; the other, back then, stood behind a clunking single-lens reflex. What I felt was a jolt between the two of us. Coming here again had brought the shock of change. It conjured an act of revelation, as if the whoosh of a red curtain had exposed my blindness to the slow, incremental transformation of the last ten years – each shift small enough to seem benign, until I no longer remembered the world of the former self.

The distance between those two worlds, through the lens of this place, had made the invisible visible. Their sudden collision had cast the differences into shape.

In the here and now, I found myself a modern-day Septimus Smith, caught in an algorithmic world. The walls around me were unresponsive, my mind tethered to things I could not see; the present, a steel press. Back then, I would have longed for all the bristling technology that I now carry so wearily. I had no idea what sacrifices I – and the world around me – would make; yet the true luxury of those earlier days was the space they allowed inside my own head – the unadulterated freedom to think of nothing, to feel the moment as it was, to hope and to imagine. Such precious commodities in a society that constantly presses us for attention.

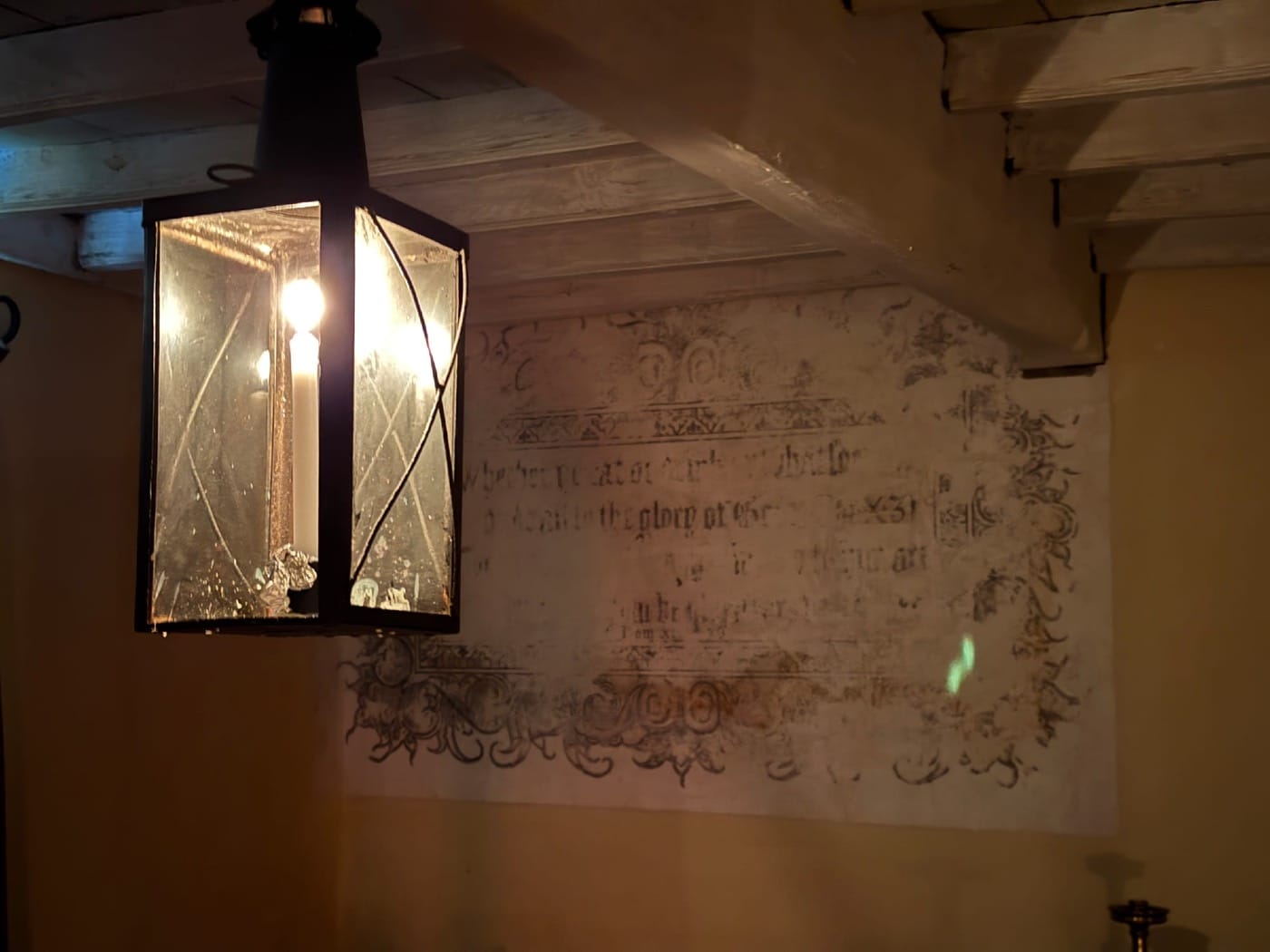

I think of the people that lived here so tangibly at Cowside in the eighteenth century. The Slingers’ Anglican faith was painted on the walls in the parlour - an expression of identity and belonging at a time when Quaker families further down the dale shaped their own way of worship. Two distinctive ways of seeing the world.

The Slingers’ affirmations were part of the long, complex permutations of centuries of anxiety over faith and identity - an unease that had only begun to soften after the Act of Toleration in 1689. The dales themselves became a kind of microcosm for the country’s slow movement towards tolerance and coherence. Over time, these declarations, like those painted upon the walls here, became less about difference and more about continuity - part of that gradual knitting-together of lives across the landscape.

My first self saw the world I lived in as an imperfect but evolving consequence of the valley’s hard-won continuity, born of its people’s ability to overcome and endure. The Slingers’ wall paintings stood as a testament to that coherence. But the second self — this present self — saw more keenly the fragility of that assurance; how easily such certainties can fade. The paintings now seemed less like a conclusion and more like a question.

It felt as if my former self was having to remind me, through the fog of the present, that tolerance isn’t dependent on the shifts and vagaries of circumstance; that it is a condition woven into the folds of what it means to feel right with oneself — incorruptible, enduring, the best of what a human being can strive for — and it is in that very striving that each and every one of us remains redeemable.

I might observe the Slingers’ fictions and their factions with a kind of snobbish objectivity from the ‘progressed platform of my present’; yet my life, and all that sustains it, depends directly upon people like them – their labour, their quarrels, their hard-won accord. My simple freedom to sit and have a coffee without anxiety, the freedom to be bored, to walk my streets safely – these are the fruits of their endurance, and of the evolving tolerance and accumulative wisdom held within the walls here – something that, in time, came to shape the character of the valley and the nation beyond.

Over thirty years of photographing buildings, I’ve come to realise that this is the power of places like Cowside: buildings that, through their fragments and material culture, and in spite of the world’s woes, help us imagine – not only our pasts, but the futures that might yet unfold. Such places make us stop and think, and become lenses not only into history but onto ourselves.

It takes a place like this to wake me up in an age that so often dazzles to distract. It takes a place like this to remind me of the immense depth of what it has taken for us to reach this moment - a depth so vital and yet so invisible to most of us. And because, for myself, and for many - though not all - our freedoms now seem so ordinary, so light - it takes a place like this to hold me back from the shallowness of things.

It could be that the duality of my time here, and the sharp twist between past and present, has made me oversensitive to the times we live in. Yet I can’t help but feel — through corresponding with my former self here at Cowside — that the world unfolding before us has begun to draw more and more of its shape within our interiors, where thought is never silent. It seems to herald a future, like the Slingers’ past, of perpetual agitation — of invisible worries, where rest might feel like work. One day, I might sit in my local cafe, caught up in angst, trying to find euphemisms to explain to my children the wherefores and whys of it all. Perhaps, one day, to sit in silence and think of nothing will no longer be ease but an act of defiance — of remembering what it means to belong to a world once rooted in continuity again.

I try to imagine Mr and Mrs Slinger sitting where I now sit, hand in hand, wondering what kind of world their children and grandchildren might inherit. What kind of world allows a family to sit in a parlour and think of nothing? What kind of world might let them look through a mullioned window and see others walking the dale without division or fear? What kind of leaders, morals, systems, and daily practices might such a world require?

With hindsight, we’re privileged to know how that unfolded; and with a touch of grounded watchfulness, to comprehend what ingredients allowed that to happen — lessons that ask us, like the Slingers, to imagine anew.

And perhaps it is here, in the act of imagining, that our survival lies. To have a future where we can sit in a parlour or a cafe and think of nothing may be one of the most priceless things we can ever hope to envision.

It seems to me that now, more than ever, it feels essential to shine a light on the past — to help us navigate what lies ahead. Can you help support me and keep the Digest alive?

Lots of Member Benefits

Support The DigestCowside.

This is part two of a two part digest on Cowside. If you missed part one and would like to know more about its context - click below:

Cowside, with its origins in the late C17th, is unique in that it is, by and large, untouched. Set within the upper Langstrothdale valley it is a place apart. You can learn more about its history and the people that lived there by clicking here.

Access to the farmstead is via wheelbarrow from the riverside beneath.

Exterior

The farm has that classic long-house feel, incorporating the barn and domestic accommodation.

The Poultiggery

I was mesmerised by the Poultiggery - not because of its function but because of its wonderfully compact nature built from natural materials - a kind of Swiss army knife of a building,

Many Dales farms kept a few hens and a pig or two for their own use, feeding them on kitchen scraps and dairy waste. The Cowside piggery, probably built in the 19th century, seems to have formed part of a combined hen and pig house — once known as a poultiggery. Hens occupied the upper floor, the pigs below, sharing warmth while the pigs helped ward off predators. At Cowside, the pigs entered from the north, beneath a loft floored with stone slabs. Hens, usually tended by the farmer’s wife, foraged freely and returned to roost in nesting boxes along the walls.

The Interior.

The Hallway

The hallway is one of the most intriguing spaces for me - it offers the first glimpse into the building and then a framed view to the outside world. I love the rectangular overlight and the coat hooks too.

Parlour

The main living room of the house, the parlour retains its original limewashed walls with painted biblical texts added by the Slinger family. A large fireplace provides focus. It’s comfortably furnished with traditional pieces, offering space to read, relax, or reflect on the building’s layered history.

Kitchen

The kitchen forms the heart of Cowside, with its large stone flags, exposed beams, and welcoming ingle nook once used for cooking and warmth. The deep-set windows look out up the valley side to where there was a pack-horse road.

Bedrooms

You can stay at Cowside via the wonderful Landmark Trust

Whilst at Cowside I did try and get back in touch with those former times when I visited. I sketched some of the interiors and also made a sunprint of a feather that floated down in front of me as I stood outside the door.

The analogue work acted as a kind of portal into the world of my previous visit.

Although I did succumb to the odd modern intervention:

Lots more VR experiences here for members:

For Members - Cowside Video (Exterior and Interior)

Something to whet the appetite for next weeks digest.

Click to ViewLots more video of amazing places here for members:

Kind words from a subscriber:

Andy your work is becoming wonderful, remarkable. A so-called breakdown has been milled into its constituent parts, becoming profound construction: through perception, architecture, the lens and the pen. In your Repton crypt essay a deep description of our social anxiety - and our reason to be....

Recent Digest Sponsors:

Thank You!

Photographs and words by Andy Marshall (unless otherwise stated). Most photographs are taken with Iphone 16 Pro and DJI Mini 3 Pro.

Member discussion