Welcome!

Kind words about the Genius Loci Digest

To receive your Digest is to take a long drink from a cool stream on a hot day. Your beautiful word paintings take me to places I'd forgotten. Thank you. Chris

⚡️ View the latest digest and the full archive here.

📐 My Goals ℹ️ Donations Page & Status 📸 MPP Status 🛍️Shop

🔗 Connect with me on: Bluesky / Instagram / Facebook / X / Tumblr / Flickr / Vimeo / Pixelfed / Pinterest / Flipboard

Unlike many other medieval chapter houses, the ribbed vaulting of Southwell Minster's C13th chapter house doesn't have a central pier. It's vaulting hovers over the space like a starburst during first light.

“Tolerance implies no lack of commitment to one’s own beliefs. Rather it condemns the oppression or persecution of others.”

— John F. Kennedy

January is named after the Roman god Janus who looked both ways into the past and into the future. Being a hinge month, it is a fitting point in the year to pause, to take stock, to allow the previous months to settle before stepping forward again.

For most of my career, I’ve spent much of my time photographing remarkable and visually impactful places. I’ve stood inside mighty cathedrals - buildings that assert their importance through weight and scale. They are places that speak clearly of power, belief, wealth and endurance, and of the roles they have played in shaping the nation’s story.

And yet there is one place I visited just over twelve months ago that has remained with me. It is a place so meek in stature and form, that its significance didn’t reveal itself all at once. Instead, it has taken the passing of an entire year for its meaning to settle. It is a place that has accompanied me through the seasons, like a charm of goldfinches - appearing unexpectedly, inexplicably, yet returning again and again along the wayside during moments of reflection.

In late December 2024 I spent a day photographing Farfield Friends Meeting House (near Ilkley in Yorkshire), pocketing the photographs through my lens and then reviewing and finalising them in January last year - hinge month, hinge process - where all the creative intensity of that day lay in an in-between state - diluted into the pixels on my hard drive.

Janus is not only the instigator of the first month of the new year, he is also the god of thresholds, of doors - and, if there were a place where we might list the significance of doors in our nation’s development - the simple door at Farfield would be high up on the list.

For me, the power of a place is amplified when significance is expressed through function, and at Farfield I have rarely encountered anything as potent an expression of time as this simple doorway. The year 1689, cut into the stone above the entrance, is itself a threshold.

It marks the passing of the Act of Toleration – not an instant of full acceptance, nor the end of persecution, but a loosening and measured permission to exist. Farfield is not about celebration or triumph, but about survival after the easing of centuries-old pressure.

This little place that looks like a house stands as a marker in Britain’s incremental movement towards toleration. Its significance lies in what it represents rather than how it presents itself - a shift in the nation’s moral and civic life brought about through restraint, patience and persistence.

In his book The Last Wolf, Robert Winder suggests that cooperation was not an abstract virtue but a practical necessity for ordinary English people. The medieval open-field system – which left behind the ridge-and-furrow patterns still visible in meadows caught by low sunlight – required neighbours to work interdependently. Land was divided into shared strips, responsibilities rotated, and success depended upon compromise and restraint. From this daily negotiation with one another, a form of tolerance emerged – not as an idealised principle, but as a lived habit, shaped by the soil itself.

So it comes as no surprise when I learn that the land on which the meeting house stands was gifted by a sympathetic landowner, secured not by a short-term agreement or a gesture of convenience, but by a 5,000-year lease. The scale of that number is striking. It stretches the imagination beyond individual lifetimes, beyond dynasties, beyond political moods, beyond land grabs and profit and loss. It speaks of intent rather than expediency, of hope anchored into the future. This was toleration conceived not as a temporary concession, but as something worth protecting for generations yet to come.

The 5,000-year lease invites us to consider the value of the long view. Continuity of this kind steadies societies, giving people confidence that values can outlast conflict, and that places of refuge may endure when fashions and regimes pass. It encourages care over haste, stewardship over extraction, reminding us that we are temporary custodians within much longer stories, and that our most meaningful contributions are often those that endure rather than those that impress.

Architecturally, Farfield is a study in restraint. Vernacular stone, modest openings, a simple pitched roof. Inside, the space is stripped of hierarchy and display. There is no altar to command the eye, no axial drama or vertical striving. Benches face one another. Limewashed walls corrugate the light. Timber beams are laid bare - another material posture towards openness and honesty.

In a world repeatedly drawn towards excess and amplification, Farfield suggests that restraint itself can be a form of strength – one that clarifies purpose and makes room for others rather than elevating the self.

It is almost as if this place has ripened for our age - not an argument or an ideology, but containing values that feel shared, human, and incorruptible.

And yet, because humans are human, restraint within these walls doesn’t entirely suppress expression. Within this disciplined simplicity there is a single and tender deviation - a turned baluster, carefully shaped, offering a moment of rotund comfort. It feels out of character, and because of that, all the more telling. For me, it’s another expression through the building of relief finding form - a small release of joy that is unmistakably human. Even here, in the most restrained of places, the makers hand did linger where it should have hurried past.

As I worked my camera around Farfield and turned it into pixels - its simplicity dissolved into something that felt deeply cleansing. Seeds were sown here, however indirectly, towards broader ideas of dignity, freedom and mutual bearing that continue to unfold across Britain’s story.

It’s a story that is complex, imperfect and, at times, faltering - but there remains a thread of tolerance that runs through our history. And that’s why I think that this humble building is so important.

In past times when fear and discord drove people underground, they found ways of investing their ideals and counter-narratives into a building or a place. Latent with memory and meaning, these places carry their intent forward as nutrients for others to learn from.

Over the last three hundred years of its existence, empires have risen and fallen, regimes have hardened and dissolved, certainties have been asserted and undone. And yet this little house - this pocket of relief, this threshold, this simple expression of freedom - has endured. Not only as a reminder of past struggle, but as a missive addressed to the future.

This is a building that hasn’t been in regular use for many years. I imagine the landowner who leased the land for millennia looking down on it with a faint sense of unease – and yet it remains a prayer for tolerance, one that chimes across the nation. This building continues to sing a song of freedom.

Farfield’s redundancy doesn’t tell us that the work is finished. It tells us that survival itself can be meaningful. That sometimes the most important buildings are not monuments to certainty, but shelters for conscience – places that help us learn how to endure when the world feels uncertain. What I find so remarkably comforting, thanks to that Yorkshire landowner, is the knowledge that we still have another 4,663 years of this building as a totem to help us work it out.

If you’ve found something of value here, you’re welcome to stay connected. I publish work like this regularly, and reader support helps cover the practical costs of travel, time, and making the digest available.

Farfield

Sometimes buildings are worth far more than the sum of their physical parts. If there is any place worth making a pilgrimage to in this new year, it is Farfield. In a time so often described as pivotal, there is something profoundly steadying about standing within a building that teaches us how change really happens.

To immerse yourself in what Farfield represents is to be reminded that the future is shaped not only by grand gestures, but by simple freedoms that are held within the memory of buildings like this.

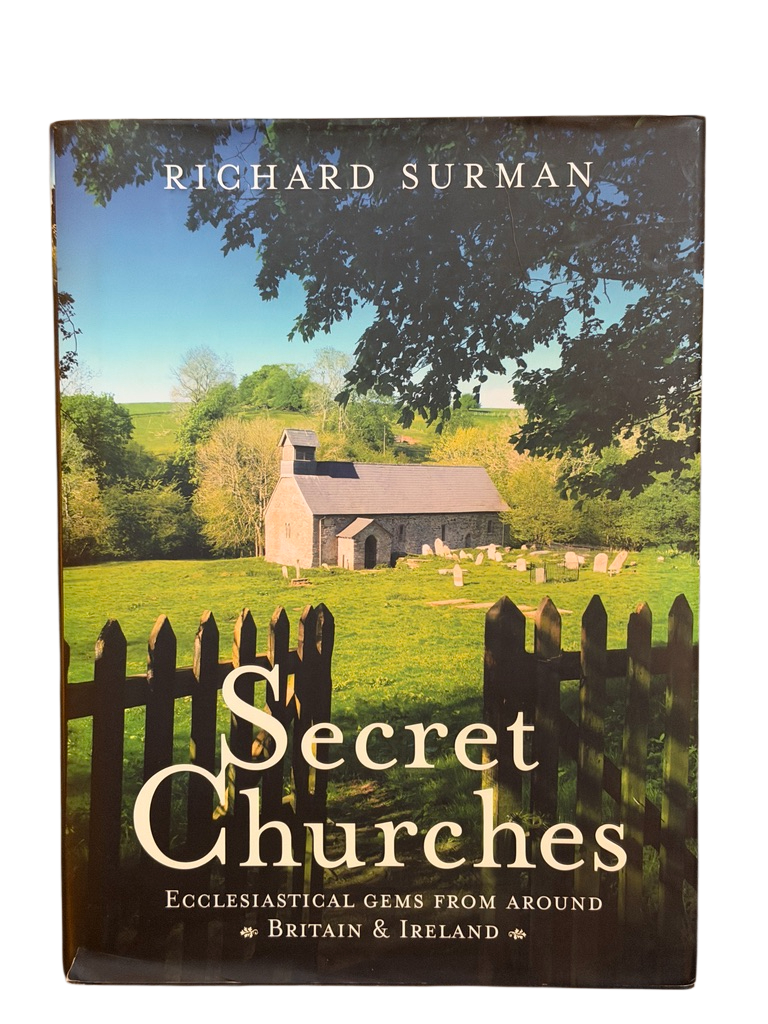

The Friends of Friendless Churches do a sterling job looking after such places. You can find out more about them and how to visit this church by checking out the link below:

The Friends of Friendless Churches newsletter is more like a small book - delightfully visual and gorgeously written. Become a Friend to receive it quarterly.

Some remarkable new finds in the latest series (including the above Thetford dig):

Wisdom sits in places, and through the curve of a simple bench end, I find myself realising that our fleeting lives are, nonetheless, an integral part of the greater whole. And through the heart of a wooden panel, I feel a glimmer of hope that humanity has a future.

Kind words from a subscriber:

Andy your work is becoming wonderful, remarkable. A so-called breakdown has been milled into its constituent parts, becoming profound construction: through perception, architecture, the lens and the pen. In your Repton crypt essay a deep description of our social anxiety - and our reason to be....

Recent Digest Sponsors:

Remember my trip around England last April to photograph several cathedrals and also St. George's Chapel at Windsor for Janet Gough's book on Divine Light?

The Association of English Cathedrals has launched a competition to find England's Favourite Stained Glass and several of the places I photographed are in the top 12 most liked from their social media campaign.

Check it out and make your vote here - can you recognise any of the photographs I took?

If you’d like to see the backstory behind my cathedral photography, along with some of the images that made it into the book, you’ll find it here:

Thank You!

Photographs and words by Andy Marshall (unless otherwise stated). Most photographs are taken with iPhone 17 Pro and DJI Mini 5 Pro.

🔗 Connect with me on: Bluesky / Instagram / Facebook / X / Tumblr / Flickr / Vimeo / Pixelfed / Pinterest / Flipboard

Member discussion