Welcome!

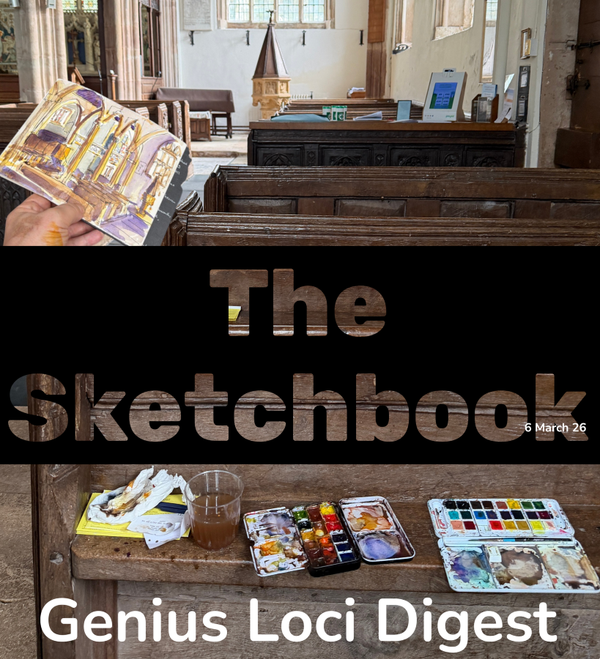

Coming soon: A day in Wells

A surprising find and an old favourite.

Kind words about the Genius Loci Digest

To receive your Digest is to take a long drink from a cool stream on a hot day. Your beautiful word paintings take me to places I'd forgotten. Thank you. Chris

⚡️ View the latest digest and the full archive here.

📐 My Goals ℹ️ Donations Page & Status 📸 MPP Status 🛍️Shop

🔗 Connect with me on: Bluesky / Instagram / Facebook / X / Tumblr / Flickr / Vimeo / Pixelfed / Pinterest / Flipboard

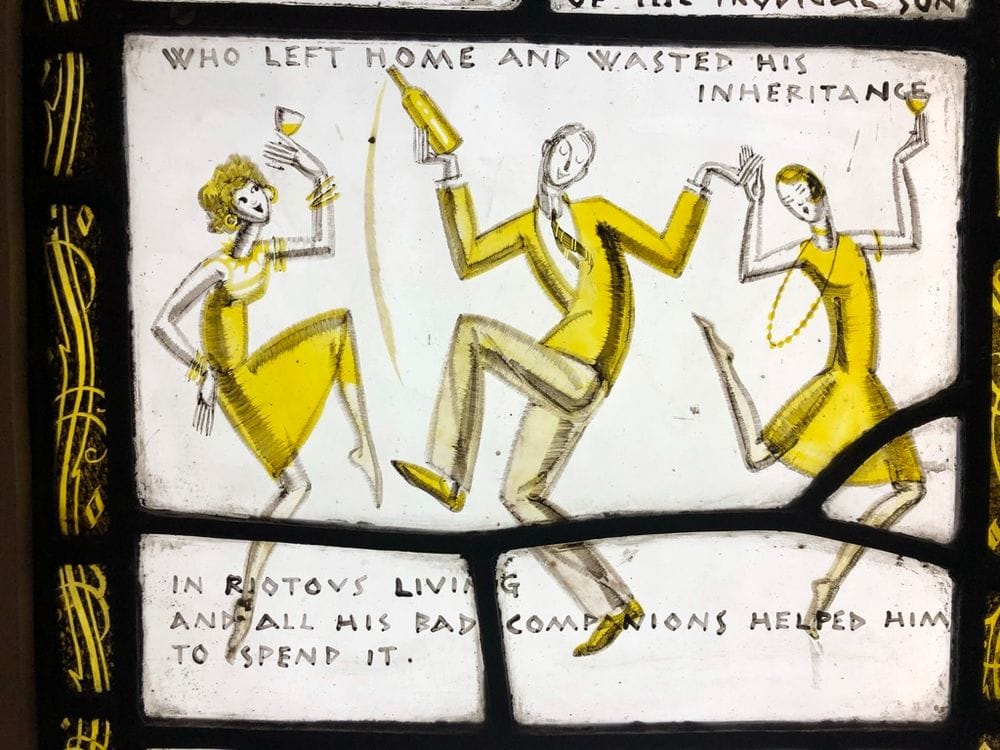

Stained glass is the poetry of light. Coloured light dappling the Romanesque at Ely Cathedral.

Although, within it's stained glass museum - there is some playful glass that's worth looking at..

“Make a Pilgrimage, Go to ancient places,

Go everywhere there are contemporary seekers.

Go in whatever way it works out.

Just Go!”

— Jini Fiennes, On Pilgrimage

The Age of Endarkenment

What each of us must do is cleave to what we find most beautiful in our human heritage – and pass it on…… And to pass these precious fragments on is our mission.

Michael Ventura, The Age of Endarkenment

It’s dark and it’s already raining as I leave the van behind in a car park that holds all the depressing traits of mundanity – litter and discarded vapes, crumbling walls, patches of oil gilding the tarmac. It’s not the most evocative place I’ve been to on my camper-van-camino.

To avoid slipping into malaise, I remind myself of another car park – the one that concealed the remains of King Richard III. How such things are so often hidden beneath the ordinary. How meaning has a habit of occurring in places that seem least prepared to hold it.

The rain thickens as I make my way towards Hyde – domestic, unassuming – sitting on the outskirts of Winchester. Like the Leicester car park, it’s hard to square its modesty with what it once held: the burial place of King Alfred. He was originally laid to rest in Hyde Abbey, of which only a gatehouse now remains.

I head to the gatehouse for respite, but the wind is driving the rain inside. There’s no escape.

There is modern housing where the abbey once stood, but a commemorative garden has been laid out, with its shape echoing the east end of the original abbey church. This is where the high altar stood and where Alfred’s remains were buried.

With rain seeping into my eyes, I stand by a ledger stone that marks the spot and feel the weight of the place rise through my feet. Of all the history I was taught at school, it was Alfred’s story that stayed with me. Not his miraculous defeat of the Vikings, or even his embryonic contribution to the forming of a nation – but his moment of vulnerability.

The image that lodged deepest was Alfred hiding from the Vikings in Athelney, surrounded by the marshes of the Somerset Levels – displaced, uncertain, distilled into the everyday. A king brought low enough to burn cakes on the fire.

There is a golden thread in this story that held me during difficult times, a thread that told me that it’s possible to move forward through imperfection rather than beyond it. Moreover, it taught me that imperfection is not an obstacle to wellbeing, but a necessary prerequisite, and that to feel humbled is to feel life settle into a shape we can actually inhabit. Held within the story is also a kind of alignment – a drawing-near to ordinary lives and shared limits – a restraint and reminder that authority without humility can become detached from those it serves.

It’s easy to forget how powerful such narratives are, and how they can become muddied as we rush towards the material and the measurable.

If I were to time travel back three hundred years to this ground where the garden now stands, I would be surrounded by convicts. Remarkably – and tellingly – the ruined site of Hyde Abbey, fully known for what lay beneath it, was selected for a house of correction – the Bridewell. Convicts were set to work digging its foundations.

One observer, the Rev. John Milner, watching them at their task, wrote:

“Miscreants couch amidst the ashes of our Alfreds and Edwards… In digging for the foundations of that mournful edifice, at almost every stroke of the mattock or spade some ancient sepulchre was violated; the venerable contents of which were treated with marked indignity… A great number of stone coffins were dug up – chalices, patens, rings, buckles – the leather of shoes and boots, velvet and gold lace belonging to vestments – and the joints of a beautiful crosier, double gilt.”

The crosier made its way to the V&A. The bones were lost.

It’s hard not to read the endarkenment of that age in the act itself – sanctity overridden by utility – a disenchanted society bent on progress, desensitised to what it means to be humble.

I’ve come to realise over time that acts such as this on places like this aren’t about the loss of the physical – but the redaction and desecration of the memory, the story, the wisdom, and the nutrients of the past – the narratives lost that might yet fall on barren soil and bloom during difficult times. The violence here is not just physical but mnemonic — a society willing to break apart its own inheritance without understanding why.

Back in the present, the gardens that trace the footprint of the abbey tell nothing of the C18th desolation, but instead there is an artist’s contemporary intervention – a glass outline of the vanished building. A kind of looking glass. Ghost walls that assemble as you peer through it – an attempt to acknowledge what is no longer there.

For a time, Alfred’s bones were thought to have been moved to St Bartholomew’s, opposite the surviving gateway. The remains turned out to belong to a medieval woman, but later a box of jumbled bones taken from the site of the high altar was analysed. Among them, a fragment of hip bone – from the right place, of the right sex, from the right date. Experts are now convinced that it either belongs to Alfred or his son, Edward.

All of this sits with me as I walk on through the rain towards St Bartholomew’s. What is it with the veneration of old bones? Perhaps we’re not seeking proof at all, but orientation – a way of touching the values Alfred’s story seemed to hold.

When I arrive, St Bartholomew’s is closed. The builders are in. I take shelter in the porch beside an electrician, but there’s no respite here.

I feel a sense of disappointment. I can’t access the church to photograph it, and Alfred’s presence is absent from this place. The rain is relentless – abrading the edges, rinsing away distraction, narrowing the field of thought. I feel like Alfred in the marshes – stripped back into the self. But, unlike Alfred, I admit defeat and set out back to the van until I see a sign – a way marker, a token.

It’s a Camino Inglés sign. A sign for the St James Way – linking this ordinary street to a route that eventually leads to Santiago de Compostela in Spain.

I read later that the route was conceived and refreshed recently – a modern take on where it might have been, gathering the presence of Alfred into the lanes, boundaries, crossings, and littered car parks. It’s a re-threading of the mundane into something truly special – a reminder that Alfred really is beneath the car park as much as the paving, the dustbins, the kerbs – and my own skin.

I’m struck by the thought that this story of Alfred finding strength through reduction and plucking success from the jaws of defeat isn’t bounded by geography or belief. That it remains available to all through the shared movement of this Camino.

Let’s burn cake together.

I turn and begin to walk back along the camino until there’s an interruption – an intercession. High up on the side of a building, down a street to my right, I spot another sign.

It’s not a way marker, a bone or fragment or theory – but it’s something that is completely relatable. A pub – but it’s not just any pub, it’s the King Alfred.

The timing makes me smile. After abbey sites and altar lines and unresolved remains, it seems I’ve finally found him.

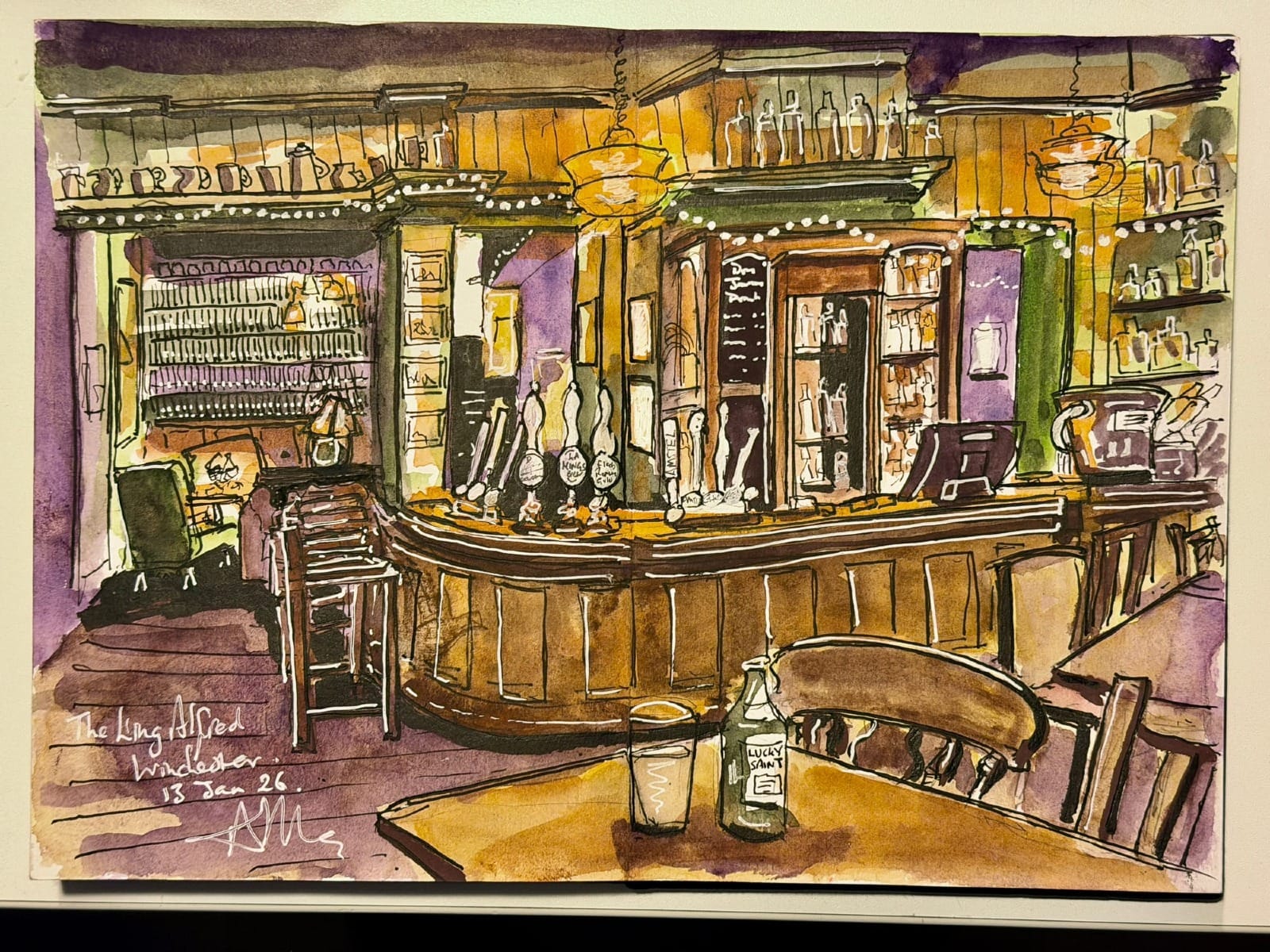

Inside the pub, the shift is immediate – warmth, welcome, timber and glass, food and drink. My shoulders drop. My hands come back to life. Before long I’m talking, then sketching – the interior slowly assembling itself on the page as my breathing steadies. The King Alfred holds me without ceremony.

It’s not the grail I thought I was seeking, nor something hidden in earth or archive, but something resolutely human – my own Athelney. A place that offers refuge without asking what I believe or where I’m from.

Perhaps the holy grail is rarely where we expect it. Not always in the vanished or the sacredly incomplete – but in other humble more recondite places that help retain memory – when the present has been washed thin and all that remains is the need for sanctuary.

🤗 Membership really does make a difference. It keeps me on the road through winter, helps me photograph historic places for free, and keeps this digest open to everyone.

If you’ve enjoyed travelling with me this far, joining up this week also unlocks all the extra posts, behind-the-scenes content and early access to things I can’t share publicly.

Can you help support me on my camper-van-camino?

Also helps support Member Powered Photography

Support The DigestThe King Alfred

The King Alfred Pub has been added to my All Time Best Pubs Guide.

See all the pubs:

More digests on Winchester:

I stop and stare and take in a few breaths. I’m in a state of awe, but it isn’t the view here in the crypt that has made me so. I’m here to steady my thoughts - to stop and think about the enormity of something that lies within the presbytery above my head.

And so, I find myself on the cusp of a street in Winchester that is as much a sensory experience as a route from A to B, as much a passage of rights as a passageway for cars.

For Members - Winchester Cathedral in glorious VR

Behind the scenes of my 1000 mile journey and moments that shaped this shoot — including new art from my sketchbook.

Click to ViewOther Member VR's from Winchester:

Kind words from a subscriber:

Andy your work is becoming wonderful, remarkable. A so-called breakdown has been milled into its constituent parts, becoming profound construction: through perception, architecture, the lens and the pen. In your Repton crypt essay a deep description of our social anxiety - and our reason to be....

Recent Digest Sponsors:

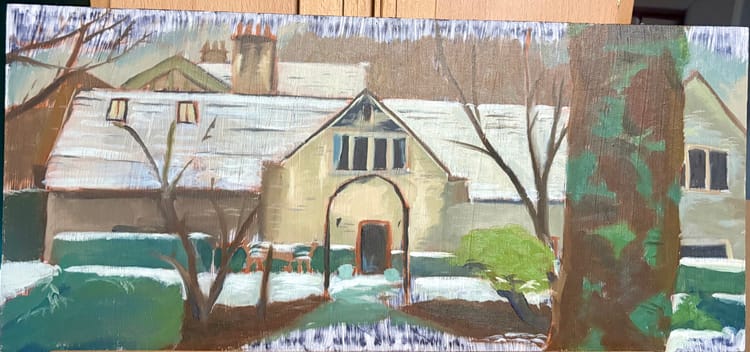

I'd like to introduce you to my son, Sam. He's a beautiful soul and has recently started writing about his journey through art. He is currently working with oils - but I imagine, knowing Sam, that there will be lots more mediums to come.

Thank You!

Photographs and words by Andy Marshall (unless otherwise stated). Most photographs are taken with iPhone 17 Pro and DJI Mini 5 Pro.

🔗 Connect with me on: Bluesky / Instagram / Facebook / X / Tumblr / Flickr / Vimeo / Pixelfed / Pinterest / Flipboard

Member discussion