The most transformative event in all of my career as a photographer occurred in a little Georgian church in Warwickshire.

All Saints resides in the village of Billesley and is reputed to have witnessed the marriage of William Shakespeare and Anne Hathaway.

On a mellowing October morning, I arrived to a scene of idyllic beauty: a small picturesque church sat within a shielding copse.

I set up my tripod and camera opposite the west end of the church and watched the sun, in acute relief, ignite the countryside.

Beyond the threshold, I caught the sun repeating its antics inside the pocket sized nave - peeking through the chancel window and raking across the gallery behind me.

As I busied about my work, the weather settled, and the sun had centre stage for the rest of the day. The burgeoning light transformed the church transept into an impromptu lightbox.

It was here that I came across two pieces of carved stone from former times - perhaps from the original church fabric where Shakespeare strutted his stuff.

One piece, beautifully carved, showed a man - enigmatic amongst a swathe of tangled foliage - being chased by an open-mouthed, bleary-eyed serpent.

The stone would have formed part of a 12th century Romanesque tympanum - a segmental section set over a principal entrance. The parable etched into the stone acted as an amulet: an incitement to the visitor - a reminder for the expected reverence upon entrance.

Beneath the tympanum lay another lump of orphaned stone: an Anglo-Saxon carving which, in the half light of the early morning, didn't amount to much in terms of visual allure. Muddied by the shadows, I could just make out the linear outline of a pattern.

Later on in the day when the sun had swung low and hard to the west, my lump of stone took on a completely different aspect, and I sat and watched, mesmerised for an hour.

I've seen such carvings in the British Museum - lit by artificial light - the snaking lines all set in equal relief - clear and pristine, yet oddly sanitised - an archaeological equivalent to a high dynamic range (HDR) image which obliterates the shadows and lays bare the rude details.

Here, though, as the light eddied and traced its way to the west, I witnessed a multi layered vista. Like a precious, baubled ring, the Saxon stone became the clawed setting, the movement of light upon it the jewel.

This piece of stone, with the assemblage of skill, time and light, propagated an act of visual magic.

As I watched - the light encroached along the transept floor, setting up a scene of sharp contrast, making the stone look increasingly stagnant.

Moments later with lime-wash as an unscripted reflector, a hardened light started to bring about an irreverent three dimensionality - a surface more faceted than textured; no detail - just an abstract - a preamble to the narrative unfolding.

Several minutes later the light had moved onto the tip of the stone - a shift in colour as well as materiality started to take place.

With the pattern within the stone softening, a deep cut frame became visible surrounding the fledgling sculpture. As I watched, with my heart rate slowing and the movement of the light now almost tangible, new chapters to the unfolding drama became apparent.

A hollowed out crows face, now a heart pierced by a vine tendril, a deepened cavity, now central to a cross like that of St. Cuthbert.

And again the slab softening - metamorphic - with the light revealing and concealing, redeeming and forfeiting sections of stone.

Acutely angled, the light enriched the relief and pricked out an etched pattern (previously invisible to the eye) on top of the interlocking ornament. The stone was no longer lumpen but particled, a sugared surface with a golden patina.

Such waxing led to stasis - an equilibrium - and the hovering of the day brought about a revelation.

For the briefest of moments, I held communion with the Saxon carver.

Out of this focused passage of time, slumbering parts of my mind (hazed out by our quick fire world) were now questioning and active - the light flux over the deep cut recesses within the stone had redeemed inquisitive neural pathways: is it one form or the other, or meant to be all those things?

Such a visual potion had transformed me into his mindset - this is how the carvings must have been intended to be experienced.

Through experiencing such a scene I'd had the briefest glimpse and parity with a world which operated upon a different orbit, an elongated time-scale.

Only a mindset with such a different gearing of time could have created such a thing. Time on an incomprehensible level.

I had been drawn into a litany of light by a mind long gone. The space between us was charged by the original spark of creativity - fuelling a personal revelation which had set apart, through the presence of absence, this simple tablet of stone as a time machine.

Here at Billesley, the carver's hand had made an hour feel like the blinking of an eye.

Unwittingly, I had been saved by an Anglo-Saxon

- an inter-generational lasso - halting me from falling off the abyss of a world where time and myth were no longer tenable, enabling me to stop, take stock and see the longer view. I'd been drawn into a place where seconds weren’t revered as game-changers, where hours felt like fleeting moments, and days begat weeks and months of fertile wisdom.

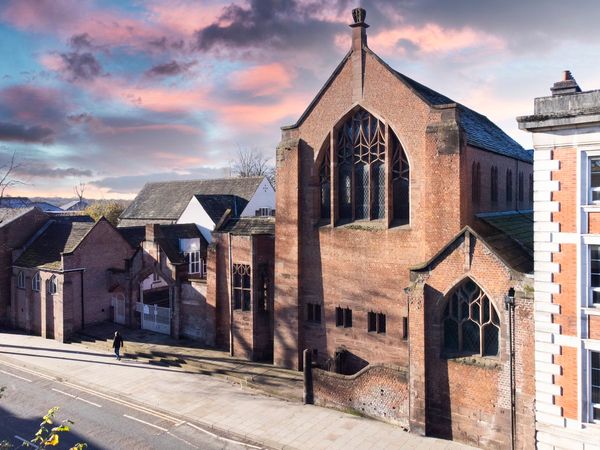

All Saints' Church, Billesley, Warwickshire

is a place that has been pivotal in my story as a creative and as a human being. Such places are rare - hovering between the past and present - full of life lessons to be unfolded and discovered. Imagine a world without them?

Because they hold such inter-generational wisdom - they are of international significance. These words, these photographs, these buildings are not the exclusive ownership of a singular person, community, nation, ideology or religion, but are part of our collective humanity.

The Churches Conservation Trust looks after churches like All Saints' Billesley and they need our support now more than ever - to keep the voices of the past pocketed within the folds of a carved piece of stone or a fading pleat of woven cloth.

This photo story was written as a part of Church Tourism Week which is an annual campaign to demonstrate that historic churches are brilliant places to visit and explore. Did you know that you can champ at All Saints' Billesley - stretch out next to the Anglo Saxon and Norman carvings? See here for more information.

Andy Marshall

is an architectural and interiors photographer based in the UK

I put my heart and soul...

into sharing my experiences of the buildings and places I visit. If you like what you see, it would warm the cockles of my heart if you might consider subscribing below, to accompany me on my travels, and get first sight of new content as soon as it is published. It can get a bit lonely out there...

Member discussion