The Whitten Tree isn’t a tree - it’s a shrub. It sits at the top of a bluff above Cinder Hill near where I live. Some time ago, I started throwing wind-blown branches at the base of the tree to mark a run, and after a few years, there grew a hefty pile of twigs. I call it the Whitten tree because I’ve heard of a tree with that name used as a meeting place. The shrub has withered and looks humbled next to its neighbours. Char and I would run past with Pep and his two boys - they too threw branches onto the tree. Later, I’d overhear his kids talking about the Whitten Tree as if it had always existed.

I've lost count at the number of sticks I've thrown at the Whitten. I’ve had sticks blown back in my face in a raging westerly. I’ve held sticks and said a prayer before depositing them; and in the convulsions of a strenuous bike ride, I’ve thrown them wide of their mark in the field beyond. On a ten-mile run, I’ve seen the perfect branch - encrusted with lichen - and carried it to the Whitten for five miles or more. There have been sticks placed beneath the tree amidst the chatter of rooks in the first dregs of daylight, sticks thrown in anger after a row, and sticks placed in memory of a loved one. With the stresses of lockdown and the daily covid death toll, I’ve ramped up my stick throwing.

One day I passed the tree and someone had kicked the sticks from its base. They'd scattered them like chopsticks along the lane. I felt fractured. It took some time to work out why I was so upset. The tree has become more than a marker of activity. I treat it as a woody memorandum, a repository of memories. Every time I add a stick, I pin back time for a moment; I stop the world spinning and mark my existence. Every time I throw a stick, I root it in an act of memory, and its grounding beneath the tree is its consecration.

The seasons are in empathy with my mental health. The summer grass grows so high that it hides the sticks for months at a time. I don’t need them during the long hours when I’m sun-kissed and refreshed. In the winter, nature pulls back her grassy duvet, reveals my buried hoard, and I feed off the memories during dark, sombre days.

I realise now that the tree has qualities that bless it with a spirit of place. It lies at the top of a local scarp; it has prospect, and there's even a processional route across a post-pandemic ditch (the M66). It’s an ideal spot to nurture an idea or belief because it is a confluence in the landscape.

Entire cities, like Chester or York, have grown from such acts: where people have marked a spot for its significance. Then the sticks become cairns, and the cairns become shrines, churches, villages, towns and cities. It’s thought that York grew from a shrine, that became a Roman basilica, that became a wooden church, then a minster - buildings popping out like Russian dolls from the original deposit of a stick or stone.

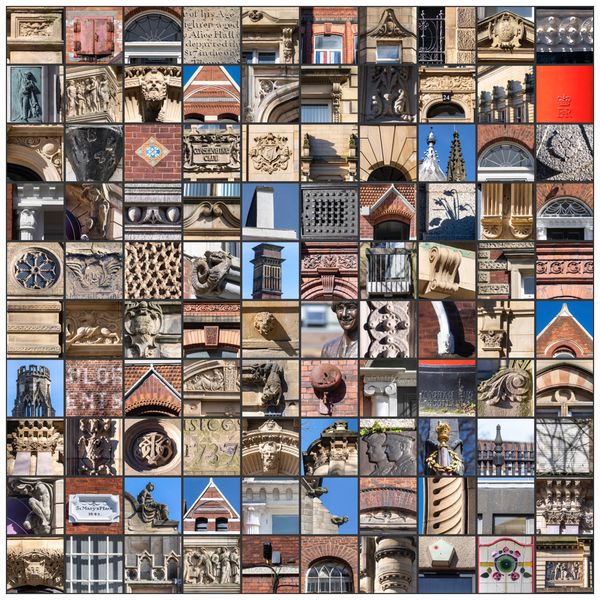

It worries me when I see our cost-driven world tear old places down or let them moulder and decay. They are live-wires to the original stick-throwing act - our woody memoranda. These places carry with them our salient memory - not shouting but hinting at what it is to be human.

Andy Marshall

Andy Marshall is in lockdown - but is usually an architectural photographer based in the UK.

Subscribe to my photo stories here

Member discussion