Welcome!

Kind words about the Genius Loci Digest

Love your website and the bio you've created. I also love finding the beauty in the simple, often overlooked, things. Tom

⚡️ View the latest digest and the full archive here.

📐 My Goals ℹ️ Donations Page & Status 📸 MPP Status 🛍️Shop

🔗 Connect with me on: Bluesky / Instagram / Facebook / X / Tumblr / Flickr / Vimeo / Pixelfed / Pinterest / Flipboard/ Fediverse: @fotofacade@digest.andymarshall.co

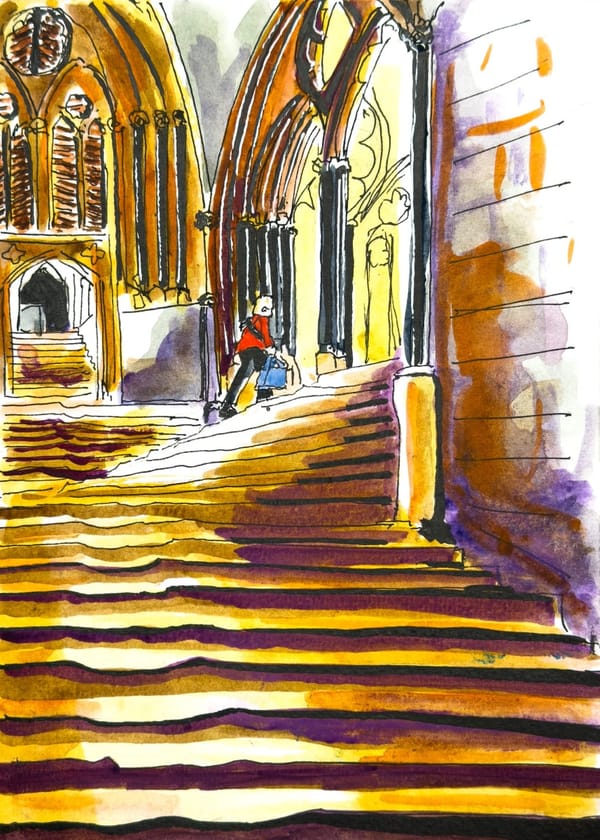

Light and Shade at All Saints', Harewood, Yorkshire.

"In short, no pattern is an isolated entity. Each pattern can exist in the world only to the extent that is supported by other patterns: the larger patterns in which it is embedded, the patterns of the same size that surround it, and the smaller patterns which are embedded in it."

Christopher Alexander

The Universe in an S-Curve

They say it takes ten years to learn a skill.

I’ve spent over thirty years as a creative — exploring places, capturing them through lens, paintbrush, and words. Perhaps the best preparation for this was a quirky combined BA (Hons) in Literature and History — which taught me to approach the past not as data, but as narrative — something lyrical, alive, and in motion.

I’m acutely aware of how lucky I am. Spending many years absorbing the world through a creative eye. The constant flow of observation, interpretation, and articulation seems to dissolve the habitual dismissiveness of modernity. It softens the sharp edges of efficiency and returns the world to something porous and participatory again.

I also know that most of us aren’t able to see many of the places I visit; or at least, at the same intensity that I do. So I hope that what I offer here is my own lens - a way of looking that can momentarily be stepped into - not just to see what I see, but to sense how it feels, and to tap into some of the wisdom that seems to be forming beneath the surface of things.

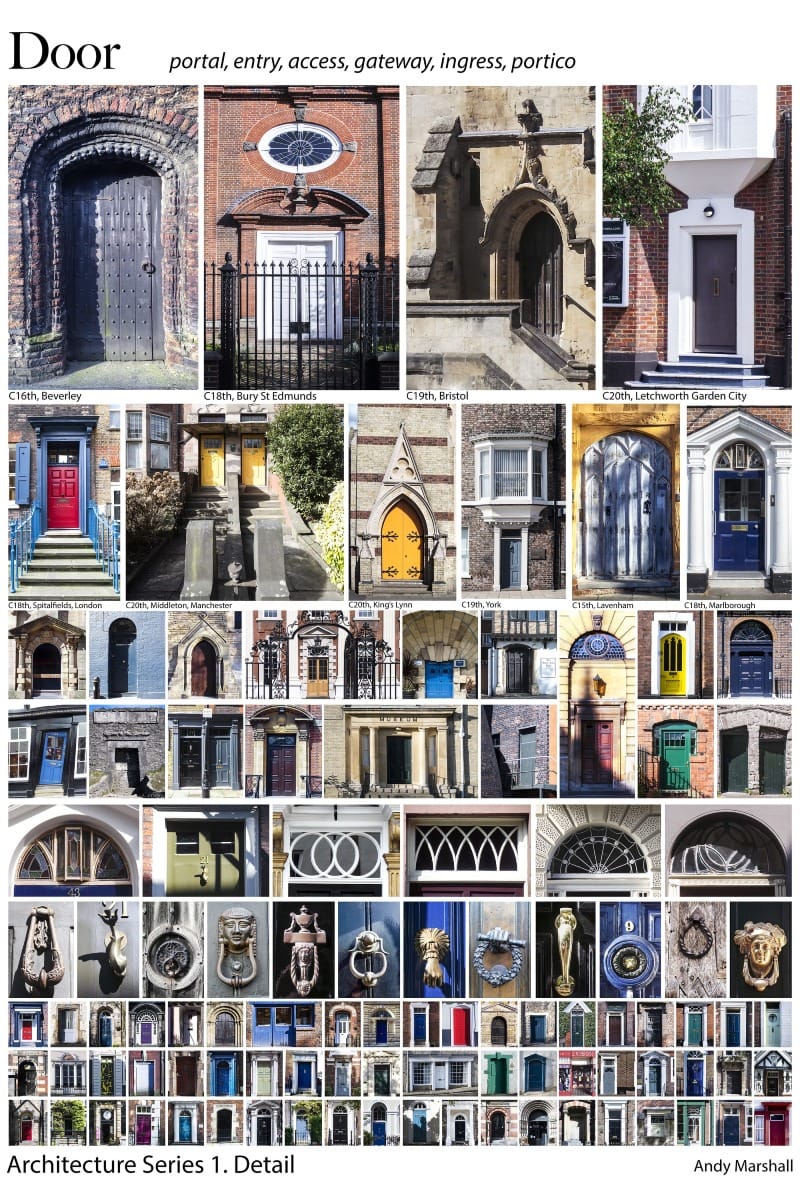

My life feels as if, since becoming a photographer, a door has opened into a labyrinth - and I’ve been moving through its turns and thresholds ever since. I share this not as instruction, but as an offering - perhaps a kind of fast-track for those unavoidably caught up in the pressures and anxieties of contemporary life. If this digest does anything, I hope it offers a brief glimpse into what thirty-odd years of sustained looking has begun to reveal.

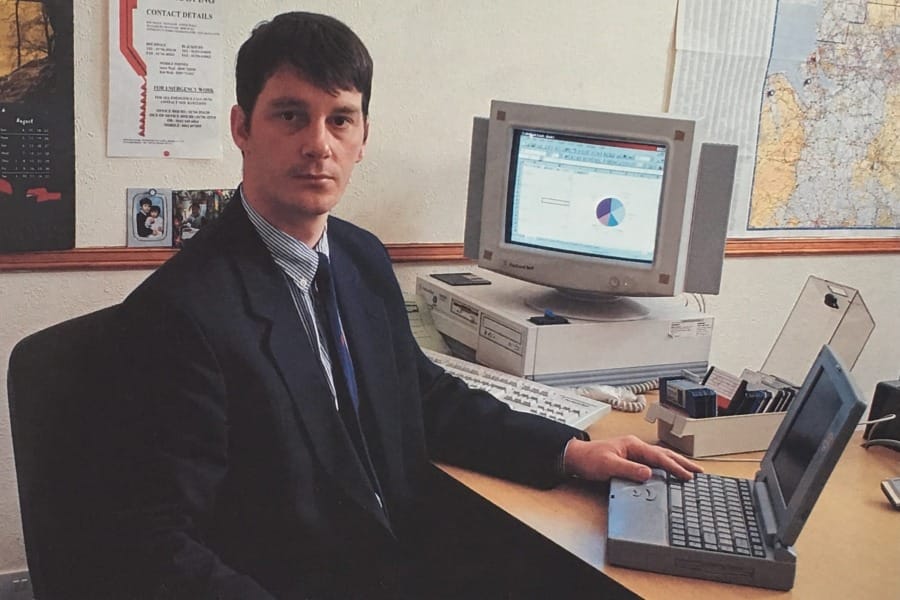

Before I became a photographer, when I was caught up in the corporate world, my vision narrowed. The world blurred into cost-benefit analysis and performance metrics. It became hard to perceive any other kind of pattern at all. It felt as though a particular worldview - and the technology behind it - was actively getting in the way of seeing.

I’m reminded of the words of Robin Wall Kimmerer:

“With sophisticated technology, we strive to see what is beyond us, but are often blind to the myriad sparkling facets that lie so close at hand. We think we’re seeing when we’ve only scratched the surface… Attentiveness alone can rival the most powerful magnifying lens.”

And thus I have found myself in a career where attentiveness is a necessary prerequisite. In the years since I started out, something has gradually washed through me like wine through water. A felt sense, rather than an idea. But it wasn’t until a recent trip that it came into pure, unadulterated focus.

The latest turn of the labyrinth came unexpectedly this month in Wells. That day, the conditions felt aligned: an ancient space of transition, encountered alone, and taken in slowly through the act of making. What emerged was not an idea, but the outline of something I had been circling for years.

Ultimately, it had something to do with pattern.

As a photographer, pattern helped me frame the world again - through the rule of thirds and through the golden section. Pattern connected me to the past more viscerally than anything else, cutting through the hardened exterior of the present and touching something deeper, older, more human. Pattern was the thing that lifted me off the floor after breakdown.

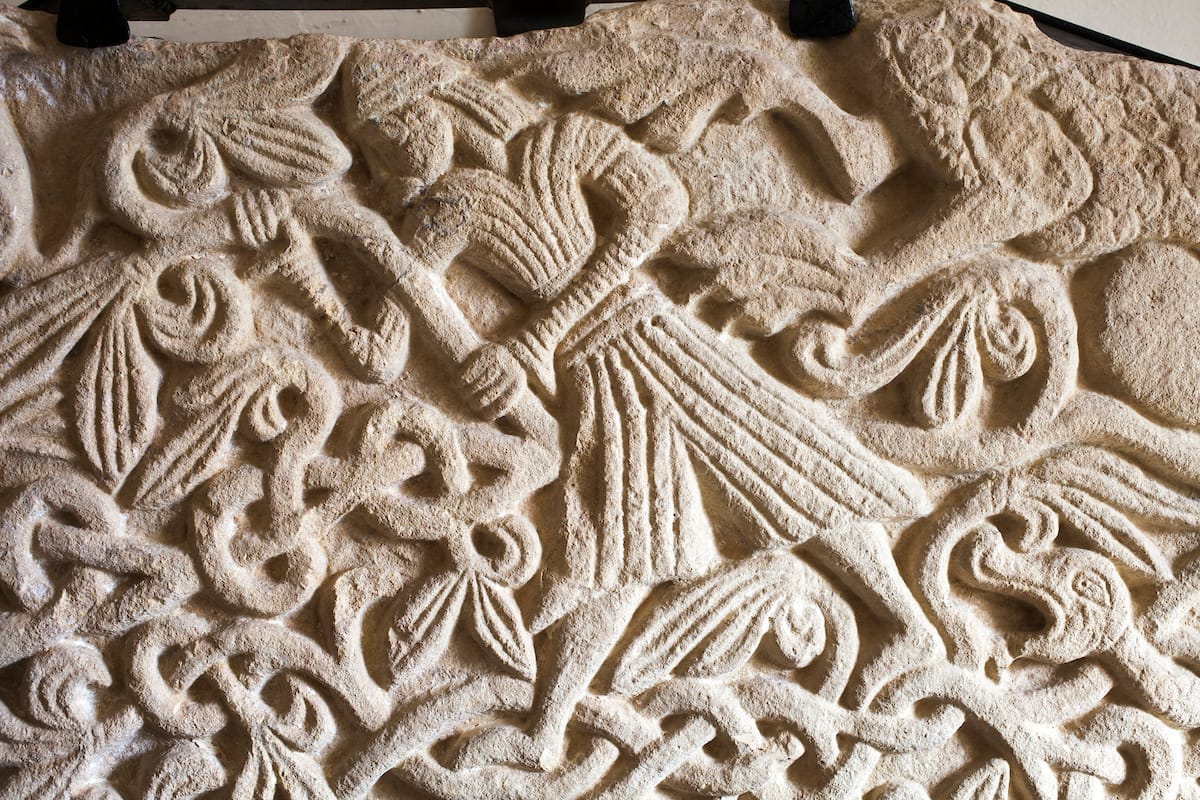

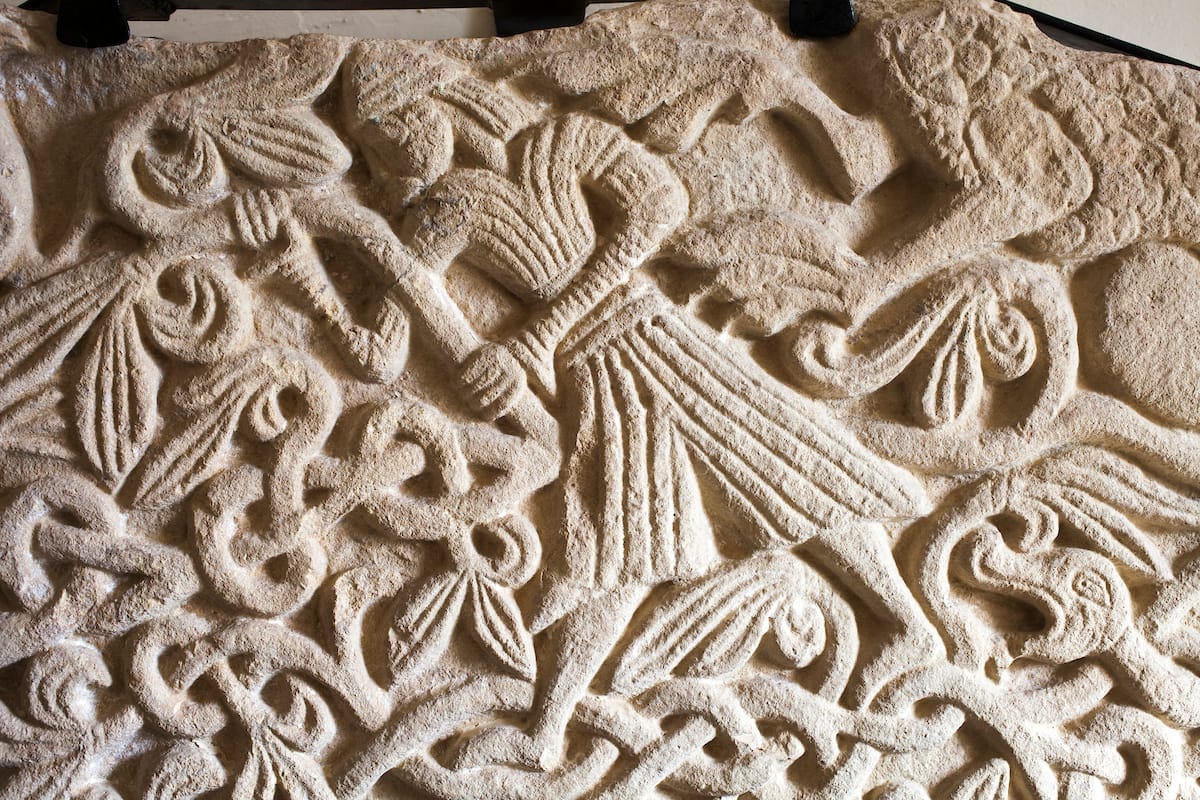

Of the material remains of the past, much of what survives is pattern: the residual arc of a Gothic arcade, the incised geometry of ancient rock art, the flowing lines of an illuminated manuscript, the melodious contours of plainsong.

What is it about pattern that is so fundamental to us?

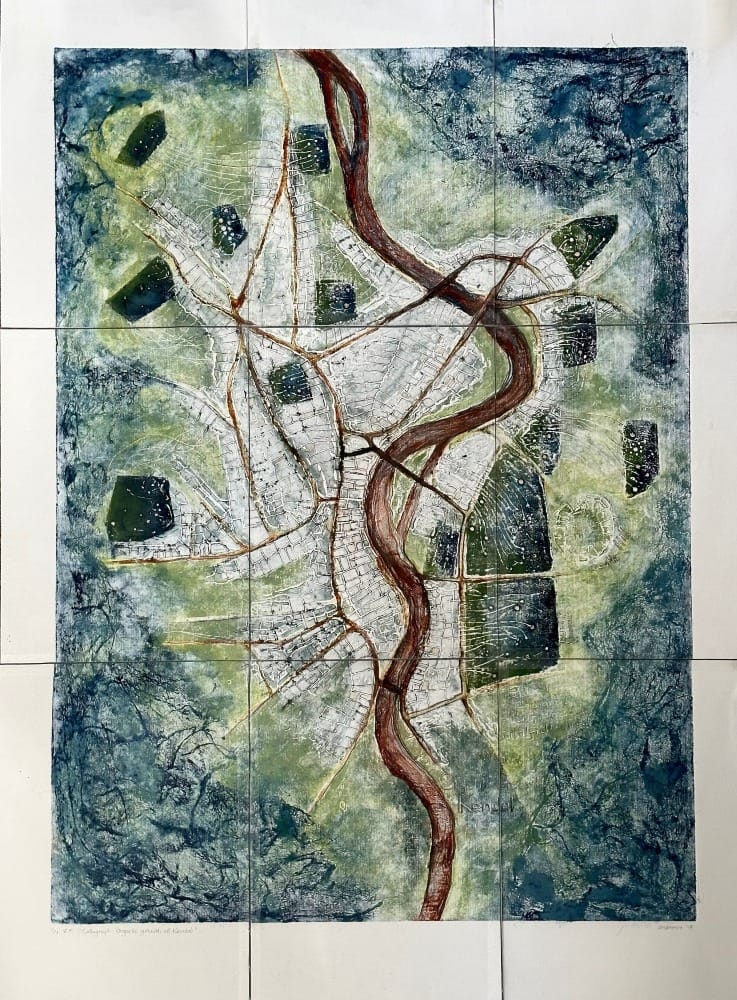

I think it’s something that is held within us. The pattern of the universe is echoed and nested through us and our world - in rivers and leaves, from snowflakes to rose windows. Patterns connect with our basic human instincts. They tie up loose ends, create pockets of safety, and invite us to lose ourselves in the curve of a circle or brushstroke. Pattern offers repetition as reassurance - a profoundly human need that sits beneath rational thought.

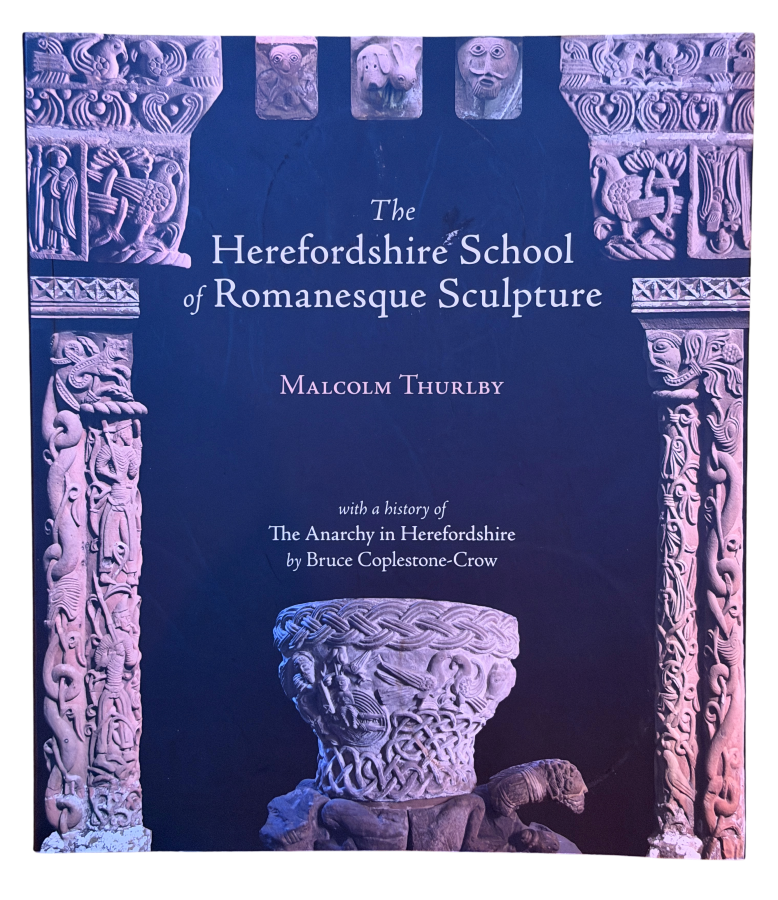

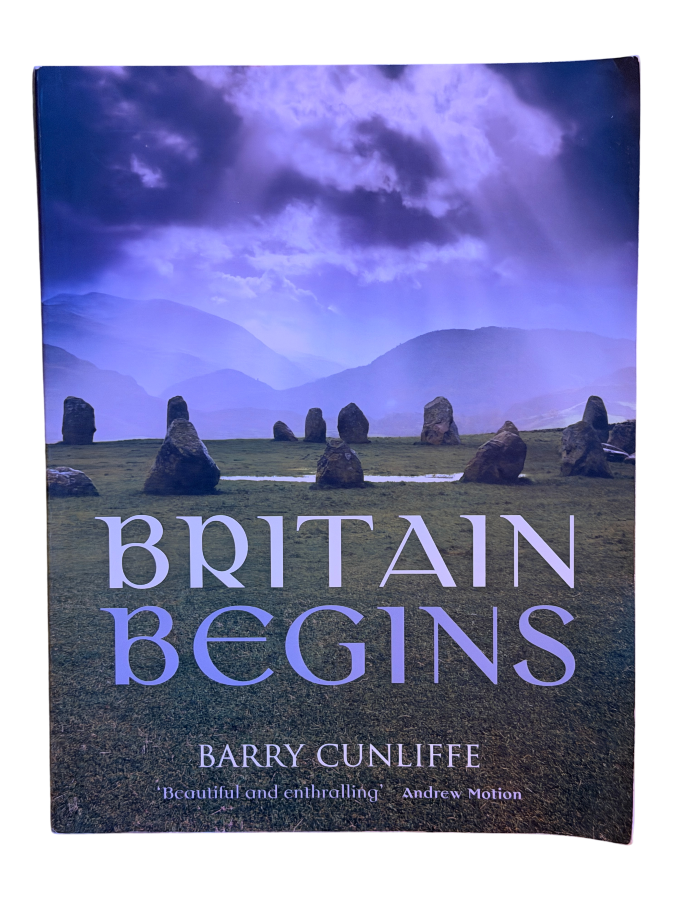

I once heard archaeologist Barry Cunliffe say that some of our earliest ancestors were nomadic. The movement of pastoral life - the cycle of seasons - imprinted itself so deeply that it could not help but be expressed in art, in its purest forms. What that reveals is why pattern can feel almost supernatural: in this case, humans become a largely unconscious conduit to their environments, carrying the rhythms of land, season, and movement forward through the act of making.

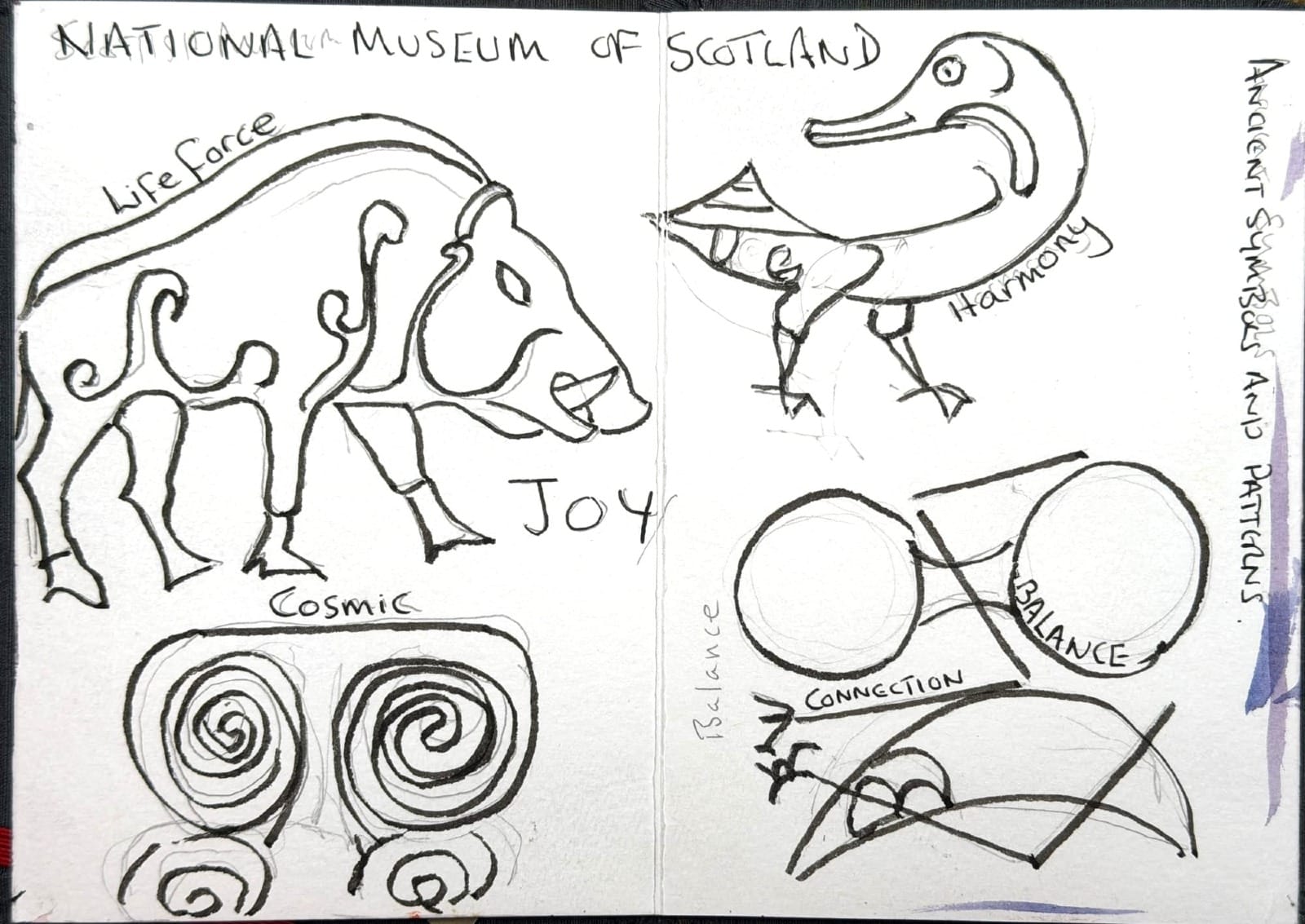

What those early patterns were doing was not decorating the world, but tuning the human mind to it. Across cultures and deep time, repeated forms - spirals, chevrons, knots, waves - functioned as mnemonic devices, holding memory in motion rather than fixing it in place. Pattern invited process: the eye had to travel, the body had to follow, the mind had to slow and synchronise. Modern psychology now echoes what ancient makers knew instinctively - that repetition and rhythmic geometry induce states of heightened attention akin to flow or reverie.

In this way, pattern became a conduit to altered states of awareness. To move with a pattern was to re-visit belonging - to landscape, to seasonality, to the greater order of things. Seen this way, pattern is not surface embellishment but a counter-script to words - a parallel language in which decoration and meaning are inseparable, where thought is carried not only through symbols, but through rhythm, movement, and felt correspondence with the world.

Whilst in Edinburgh in December, I visited the Scottish National Museum and was caught up in a world of Pictish pattern that seems to echo throughout these Isles and throughout time. When I traced their forms onto paper - they lit me up inside and I wrote next to each depiction what it conveyed to me:

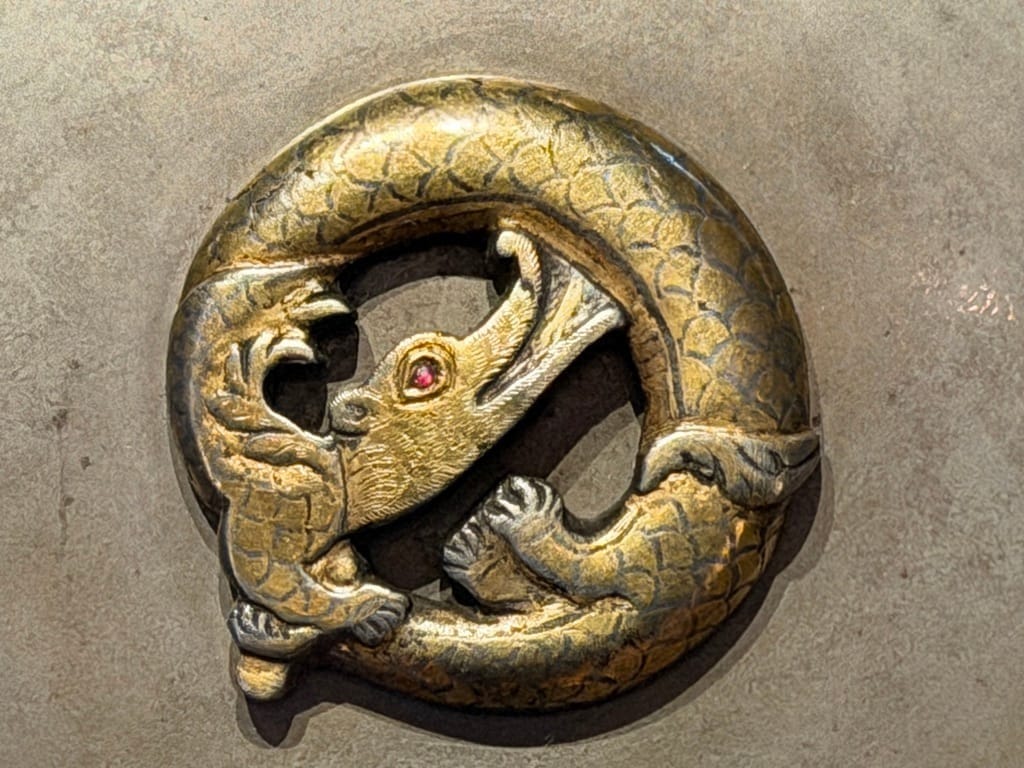

These patterns reverberate through the very best of our art: fluid lines, moving geometry, the S-curve, repeated, combined, folded back on itself. It appears in Britain’s Celtic (Insular) art, then is re-imagined through Christian visual culture. Distinct waves arrive with the Anglo-Saxons, then the Vikings.

Its origins seem to reach back to the Eurasian Steppes, where nomadic cultures imprinted pattern onto everything they made. With the Steppes acting as a kind of tipping point of the world, these forms splayed outward - into Europe, into Asia - mutating, returning, reappearing.

It’s these patterns that keep resurfacing at specific points of my career - key events that have changed the way I see and participate in the world. The door at Kilpeck. The font at Deerhurst. The tympanum fragment at All Saints' in Billesley.

The Christ in Majesty at Barnack.

The angel's wings at St. Mary, Wirksworth.

The striking correspondence between Saxon and Viking art and a Sikh shield from Punjab.

These objects don’t feel inert. They participate. They embody vitality and a kind of fluidity where movement itself becomes the subject. Their makers carried something forward, innately, into the things they touched.

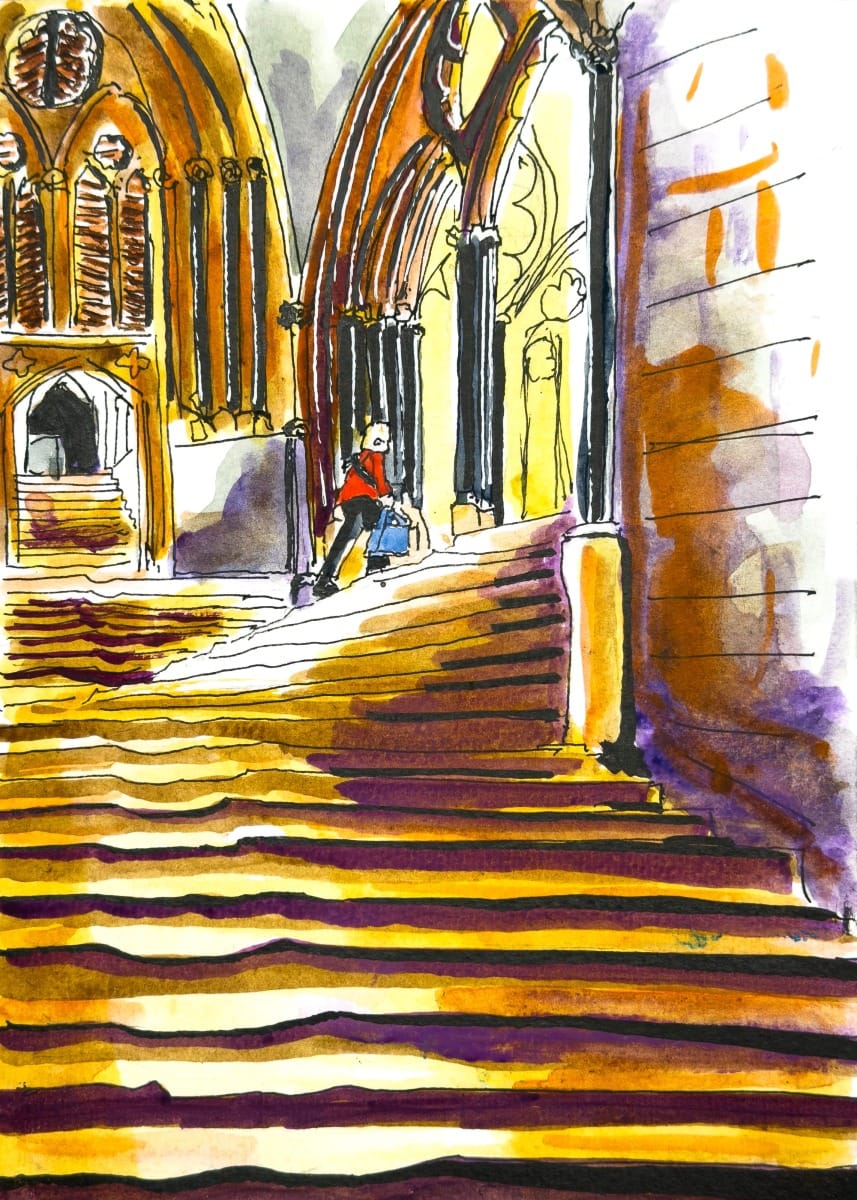

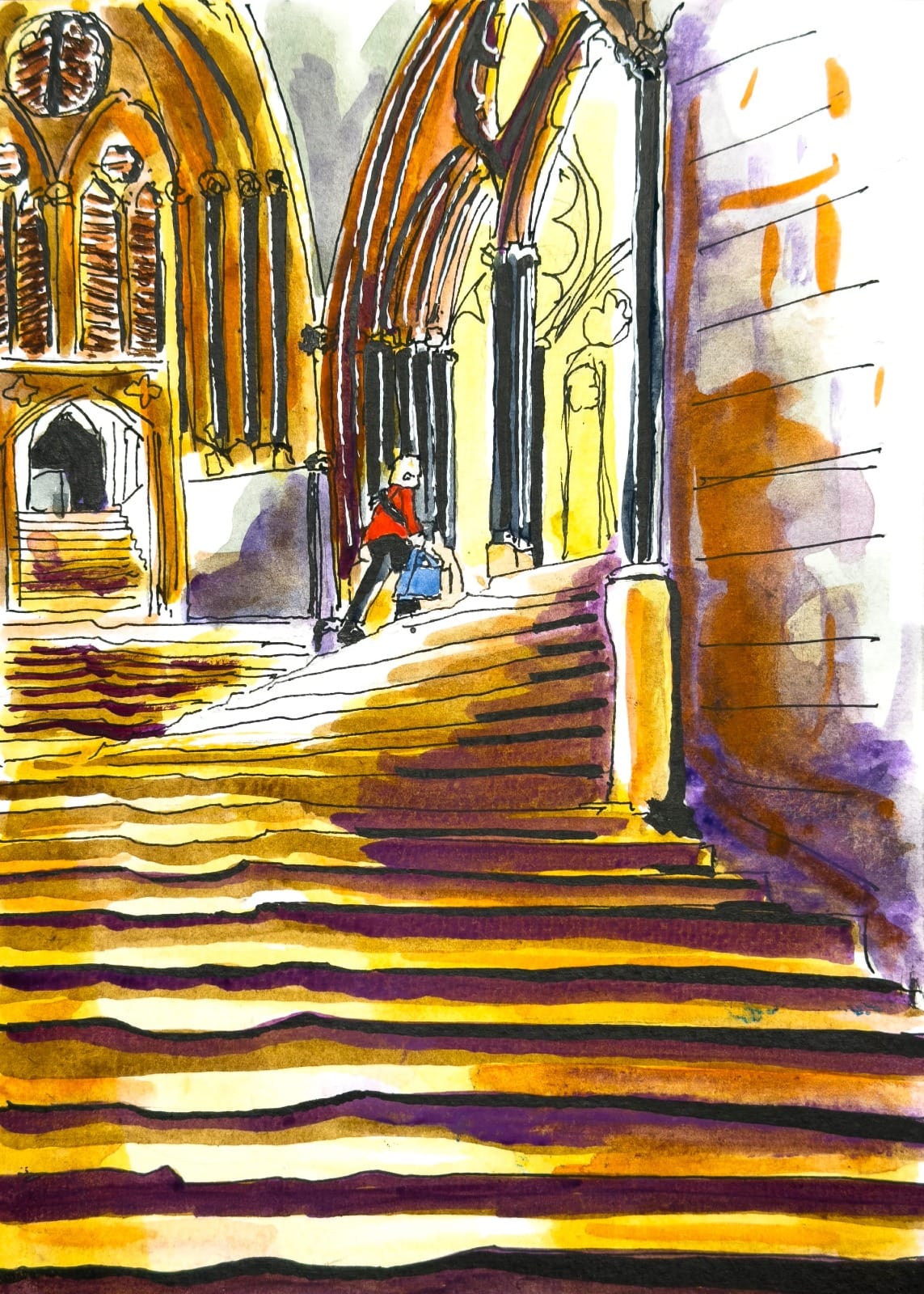

It’s a difficult thing to grasp in a world stripped of the sensorial. It seems that modernity has placed a wall of capacitive glass between our relationship with pattern. But I think I broke through it, briefly, at Wells this month, standing at the foot of the great chapter house. As I traced the worn S-curve of the steps with my eye and hand, I forgot my device and my modern self. I simply settled back into the way of things and soon realised how long I’d been misreading pattern.

Once you see it, you can’t unsee it. It appears not only in art and architecture, but in melody, in brushstroke, in the arc of a soliloquy, the rhythm of a poem, the shape of this narrative.

Heaven lies within an S-curve and not a half-pipe.

And so here I am in January - the darkest of months - back in a place nudging me toward clarity. On the page, with ink and paint, I find myself in a flow state: curvilinear marks recording not the material facts before me, but the long, slow, incremental pattern of human movement - worn into stone and set against deliberate, joyful, handmade geometry - the incidental and the intentional - connected in ways we can scarcely comprehend.

To think that, without intention or awareness, hundreds of years of separate footsteps resolved themselves into an S-curve.

With my new eyes, it all feels so absorbingly beautiful - so much so that I find myself wanting to return to every place I’ve ever visited and see it all again.

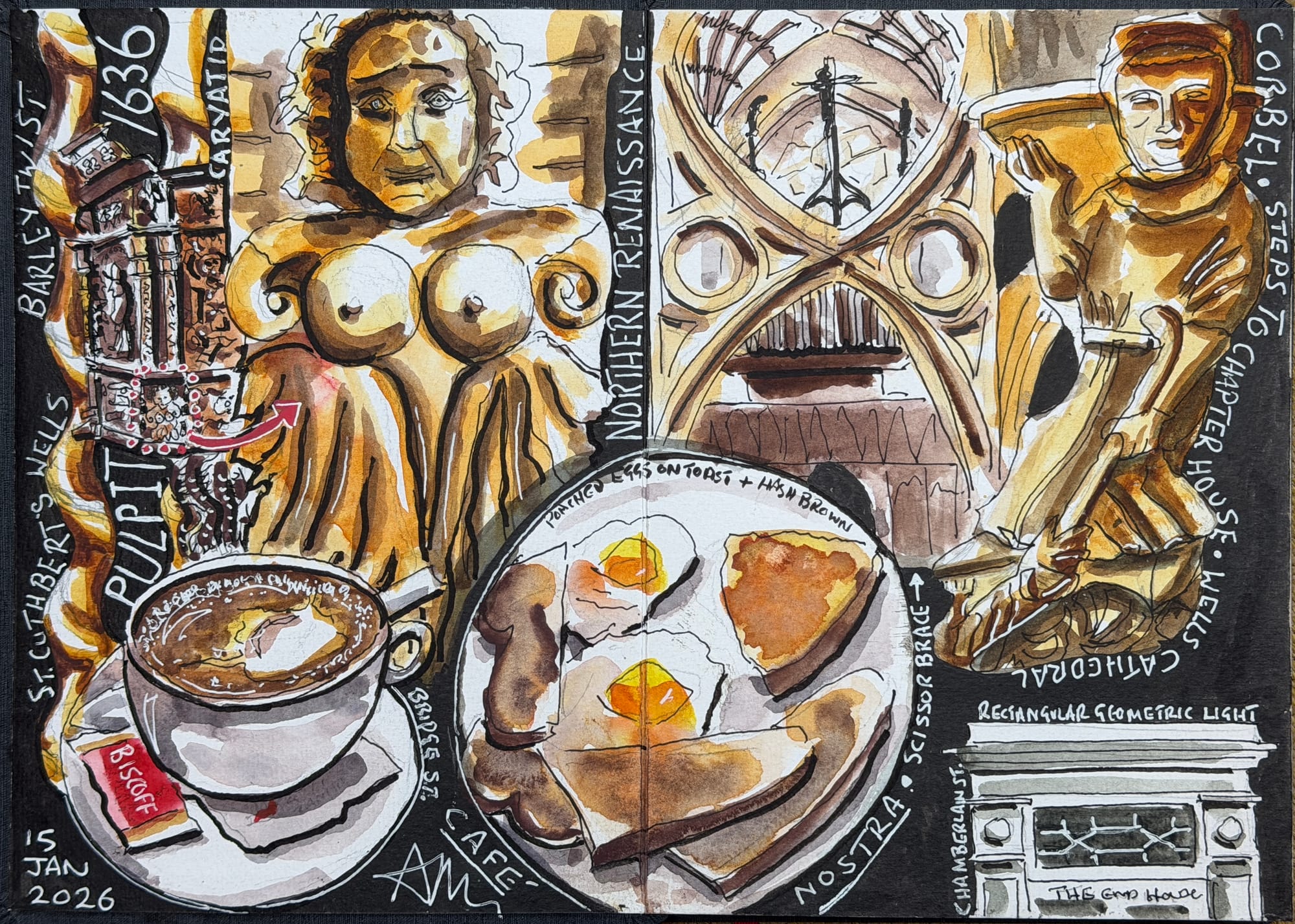

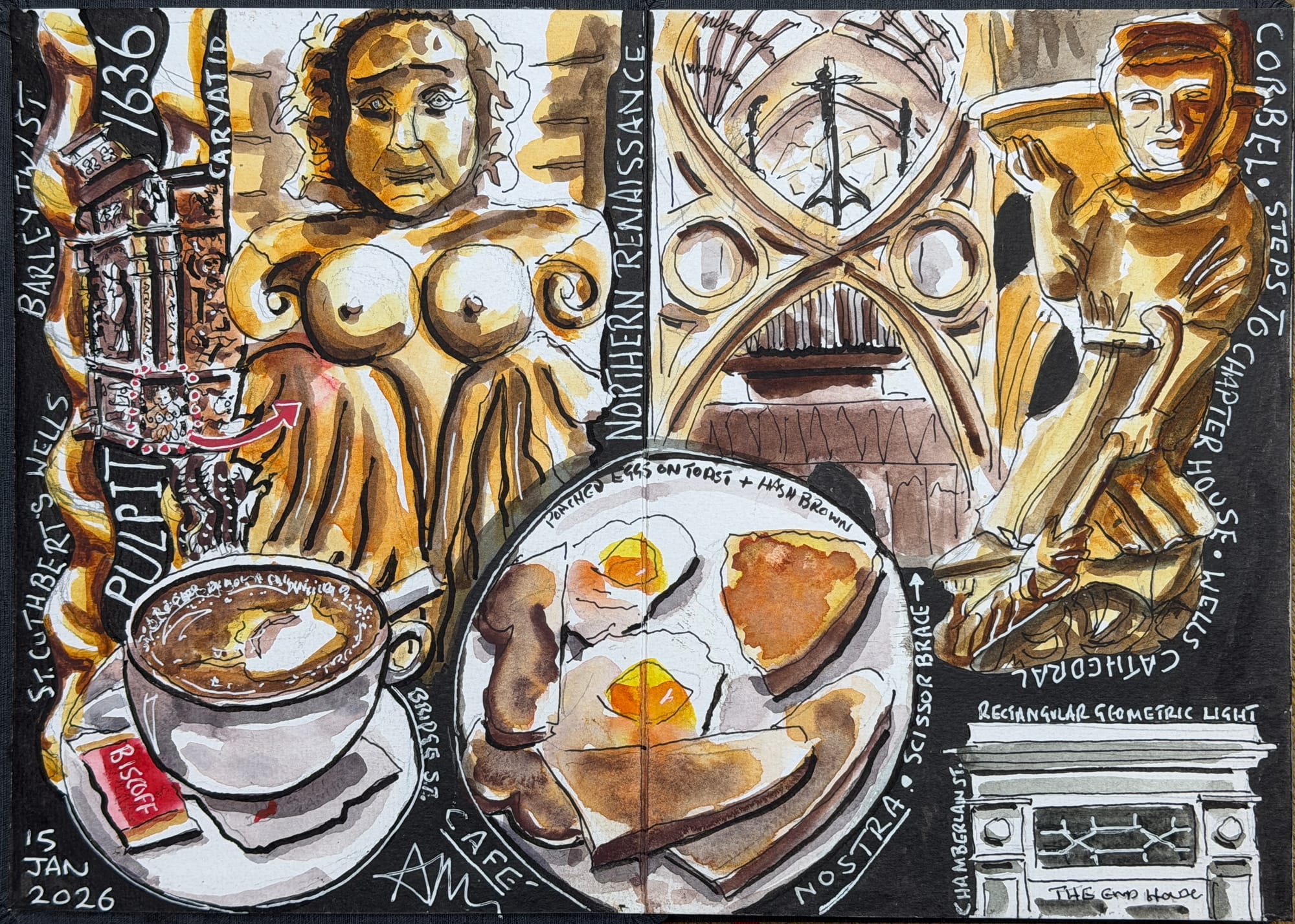

At Wells it was in everything I saw that day - the curve of a poached egg, the caryatids of St Cuthbert’s, the scissor-arch in the nave which, in itself, revealed through its shape not just its structural logic, but something closer to a cosmic truth - for writ large in the sublime language of the S-curve is the poetry of human endeavour, sustained through the passage of time.

Members of the Genius Loci Digest receive deeper essays, behind-the-scenes journeys, new artwork, and early access to projects that don’t appear publicly. If this work matters to you, joining ensures you don’t miss what’s unfolding — and helps sustain this slow, place-led pattern of my journey.

Wells Cathedral

I arrive at Wells and there's an unusual hush. People are gathered at the back and looking into the space. The chairs have all gone. It's the first time I've seen the nave without any chairs.

The guide tells me that it was never meant to have pews - people were expected to stand.

I rush back to the van to get my tilt-shift lens so that I can capture it in its original state.

You can see more wonderful photos of Wells in these digests:

St. Cuthbert's, Wells

The above is a visual diary of my day in Wells and, after breakfast at Cafe Nostra, I head over to St Cuthbert’s. St Cuthbert’s is a parish church on a grand scale and has a remarkable interior.

And a delightfully decorated Northern Renaissance font of around 1620:

Pattern everywhere I look.

My Art Work: Sea of Steps at Wells is now available at a limited edition print.

More info here

I lodged at Cheddar Caravan and Motorhome Campsite. Wells is only a 15 minute drive from Cheddar.

“The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing that stands in the way.” William Blake

During modernity, visual literacy still has the power to help us to see a tree as a thing of beauty.

The tyranny of the quantifiable…

For Members - Member's Supplement: Bishop's Palace and Garden, Wells

A remarkable journey...

Click to View

Kind words from a subscriber:

Andy your work is becoming wonderful, remarkable. A so-called breakdown has been milled into its constituent parts, becoming profound construction: through perception, architecture, the lens and the pen. In your Repton crypt essay a deep description of our social anxiety - and our reason to be....

Recent Digest Sponsors:

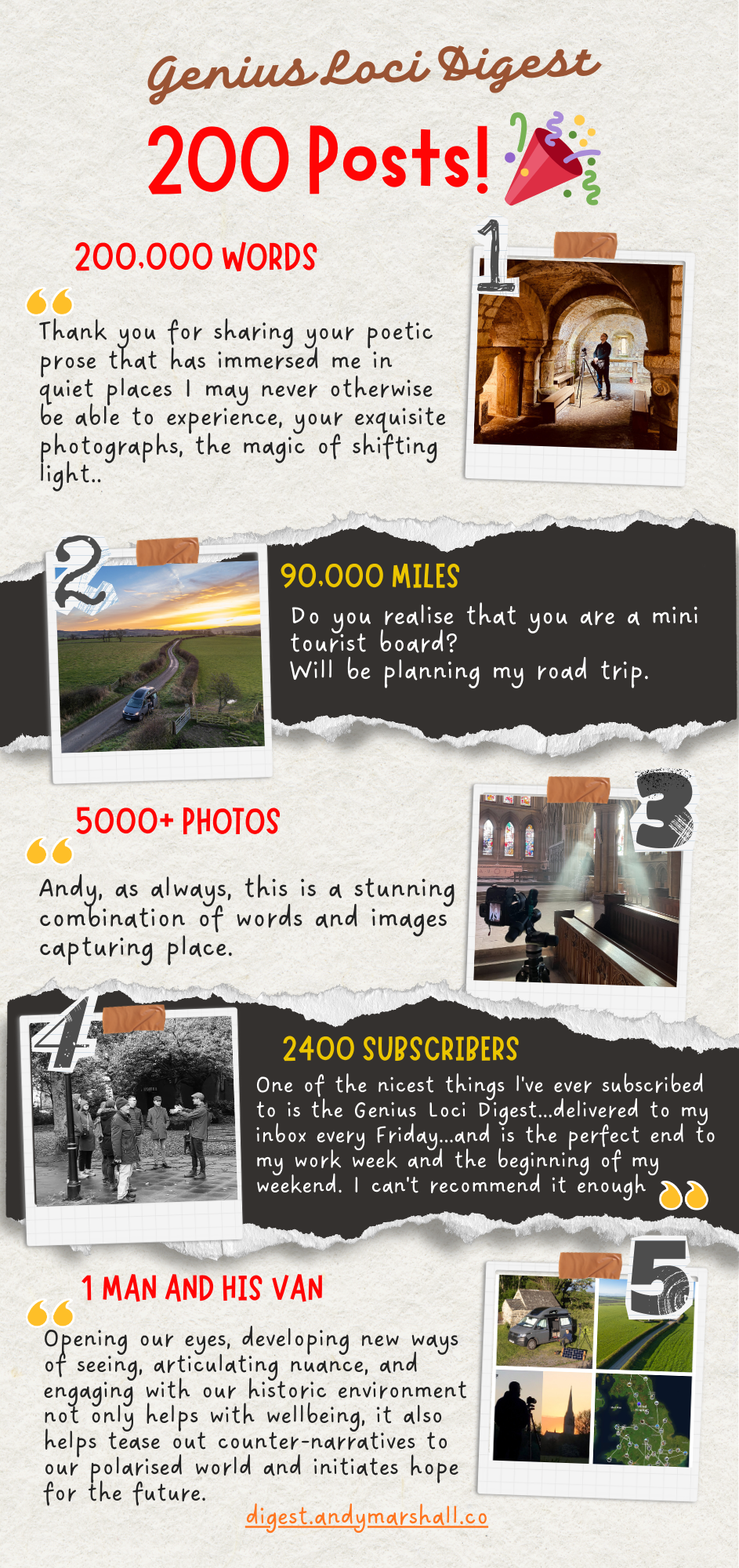

Celebrating 200 Genius Loci Digest Posts!

Thank You So Much For Your Support!

More here (plus I reveal my most read Genius Loci Digest post):

Thank You!

Photographs and words by Andy Marshall (unless otherwise stated). Most photographs are taken with iPhone 17 Pro and DJI Mini 5 Pro.

🔗 Connect with me on: Bluesky / Instagram / Facebook / X / Tumblr / Flickr / Vimeo / Pixelfed / Pinterest / Flipboard/ Fediverse: @fotofacade@digest.andymarshall.co

Member discussion