Sam and Em, my grandad spoke of Pen-y-ghent.

He pronounced it softly, phonetically - the tip of his tongue protruding slightly, padding the sharpness of the 't' with deep northern undertones.

I'm frightened I might not pass this on, might lose it - this memory from a loved one - its potency derived from days he spent within the dales that I do not know, but am kindred to.

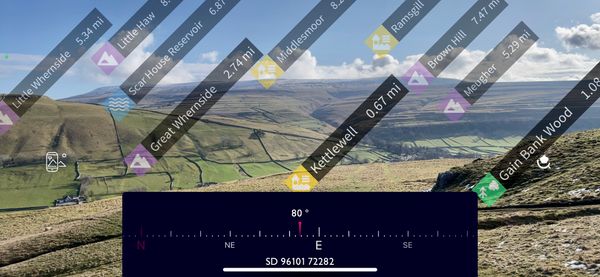

I'm walking here to connect with him, this place an affordance for envisioning him.

I see him in the gnarled stone and creaking gates, the tumbled compote of moss and lime and the battered walls crumbling over time.

The day I visit - the clouds are low and bilious - like the tobacco borealis that hung around his living room chair - amidst the sound of Cowboys and Indians chasing horses.

The sign-posts here are returning to nature - not that he would have seen - he couldn't read.

This man whose hands were deft at fixing things and wringing chickens necks, never knew the might of the pen with which I write.

I could never comprehend that

Yet, within the moment I felt him most, with the looming limestone ossuary of Pen-y-Ghent behind me, he showed me the frivolity of words, in the presence of the spindled light breaking through the dale.

Grandad

Grandad was always busy. He had big gnarled hands and he cleaned them with swarfega. When we washed our hands together, he'd give me a dollop of the green stuff, and I'd watch it miraculously clear the grime from my hands. This kind of thing was Grandad's superpower: passing on his wisdom.

He wasn't a complete saint - once, when he was teaching me how to drive in his VW Beetle - it broke down. Dad came to give us a tow and grandad let me stay behind the wheel. The engine was switched off, and when dad started to pull us away from the kerb, the steering wheel locked and I couldn't control the direction of the car, whilst being pulled forward onto a dual carriageway. And grandad? He jumped out of the side door.

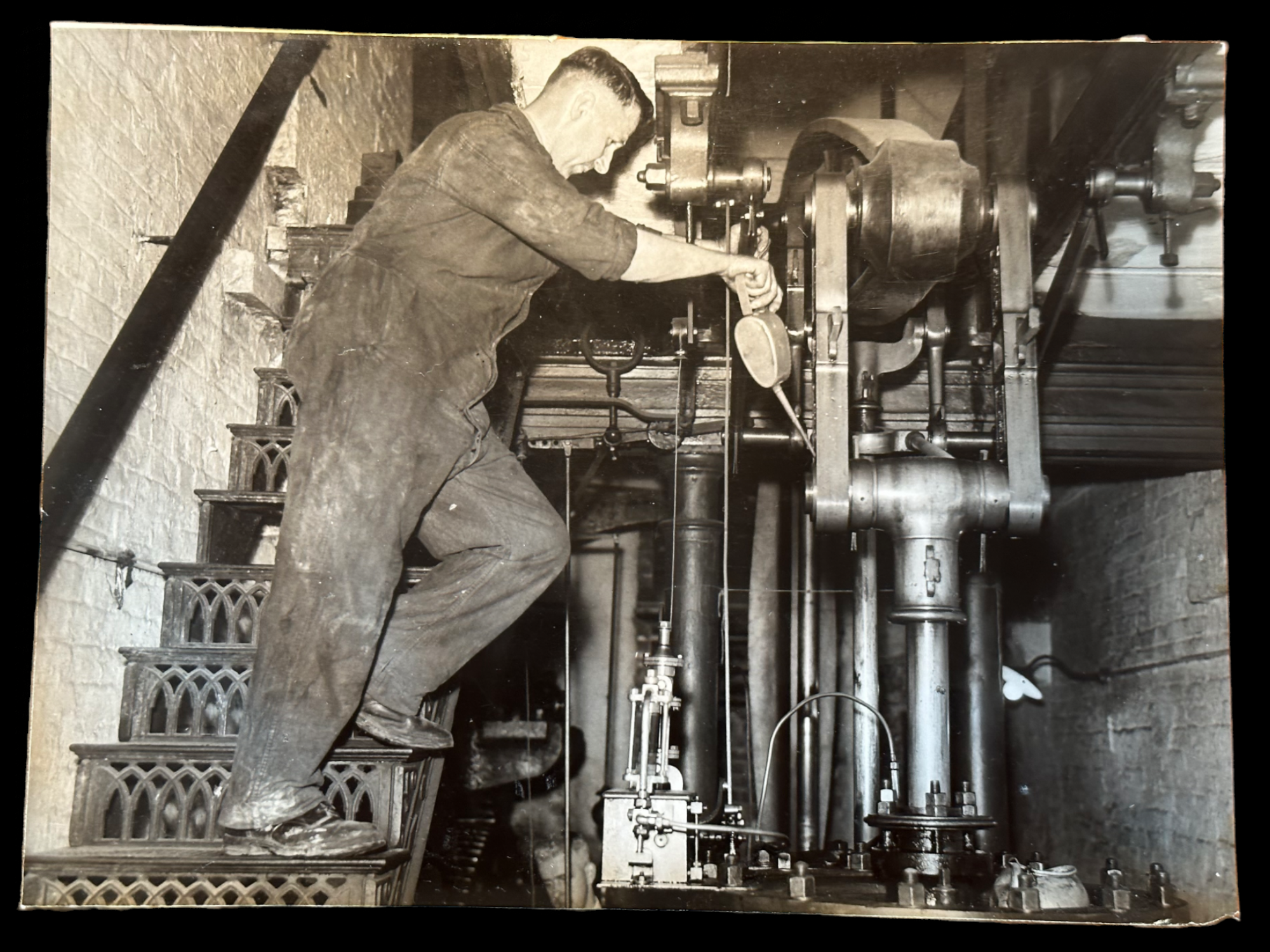

In his prime he fixed steam engines - not the toy ones, but the big beam engines down at Chadwicks.

He could fix an engine as much as a leaky roof on a chicken coop. He built his own greenhouse and glazed it. He could eat a raw onion. Most of my memories revolve around his actions in the garden: standing at the greenhouse, watering the tomatoes, pulling up wads of carrots. I also remember walking by his side, along the lane at Stakehill on a hot summer's day, with the sound of the skylark accompanying us.

Once, on the rare occasion that I stayed over at Grandad's (with my brother), I awoke and headed down stairs towards the crackle of an open fire - but before I did - I caught a glimpse of grandad through the crack in the open door of the bathroom - he was stood there in front of a mirror in his shorts and vest. His hair (which was usually immaculately greased down) was long, loose and unkempt. It is a memory I have alway kept with me because, to me, it showed his vulnerability.

Member discussion