Welcome!

Thanks for coming along

⚡️ View the latest digest and the full archive here.

📐 My Goals ℹ️ Donations Page & Status 📸 MPP Status 🛍️Shop

Adooration of the Gabli - divine portal with a singular dutch gable incorporating brick tumbling and a cartouche dated 1534. Worshipped by a wise supplicant of rough knapped flint. Strand Street, Sandwich, Kent.

“What is the meaning of life? That was all—a simple question; one that tended to close in on one with years. The great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead, there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark.”

Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

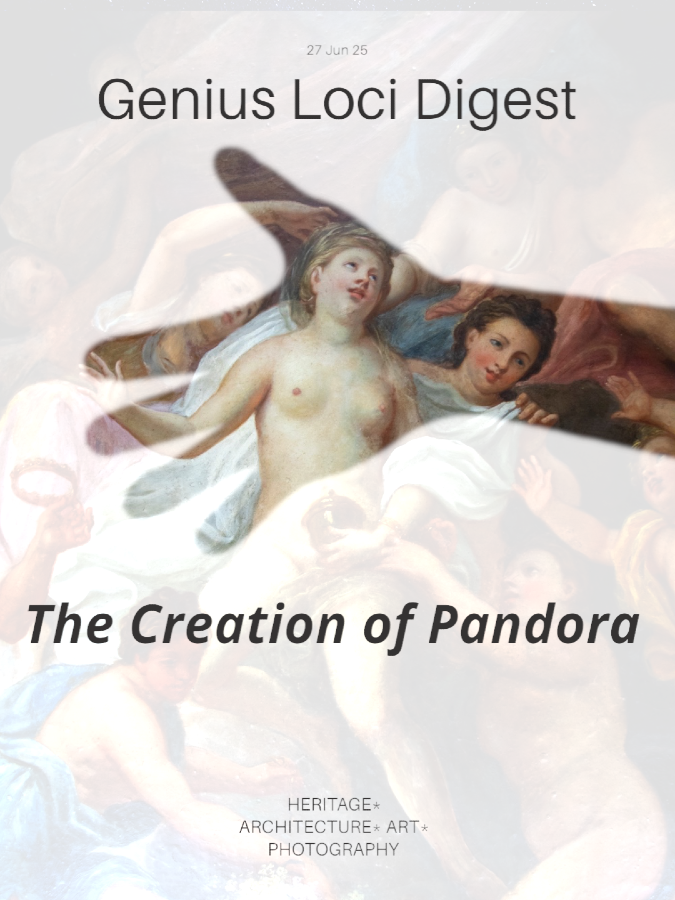

The Creation of Pandora

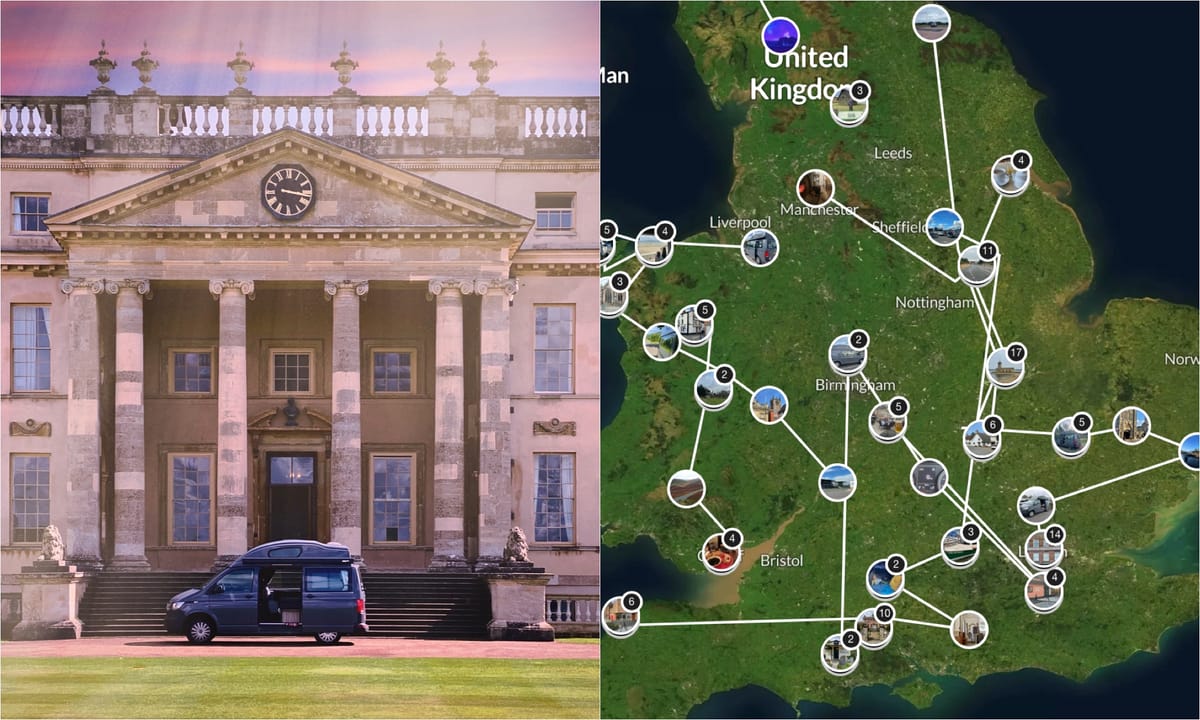

I’ve been commissioned to photograph Marta and Ryan from Chroma Conservation carrying out conservation work on a ceiling at Wollaton Hall in Nottinghamshire. I arrive early, park up, and review the instructions on where I am to park. Is that correct – am I to park Woody right in front of the hall? What a treat for Woody, I think – two design icons next to each other.

Completed around 1588, Wollaton is one of the finest examples of Elizabethan prodigy house architecture, designed by Robert Smythson for Sir Francis Willoughby – Sheriff of Nottinghamshire – in anticipation of future visits from Queen Elizabeth I.

I park up outside the imposing facade and meet up with Marta and Ryan. They tell me they’re conserving the ceiling above the south stairwell – a ceiling painted by Sir James Thornhill in 1708. Thornhill was also responsible for the painted dome of St Paul’s Cathedral.

To get to the ceiling is a passage of rights – up through a labyrinth of scaffolding and out onto a temporary deck.

It’s such a privilege to be up close and personal to the painting. Chroma have nearly completed the conservation – their skill is to bring through the vagaries of time the clarity and beauty of the original. It is no easy feat – if I were doing it, my temptation might be to replace rather than gently reveal. It takes a particular kind of patience and humility to do the opposite.

These ceilings, with their swirling allegories and classical references, are windows into a different time – not just in style but in thought. They expressed the values of those who built and commissioned them. Sometimes those ideals carried with them uncomfortable stories about power, order, and the roles assigned to gender. These artworks remain as time capsules – helping us understand how others once viewed the world.

Wollaton itself was not merely a building but a spectacle – a stage for the ideals of order, lineage and learning. Built using pattern books rooted in the Renaissance, including the works of Serlio and De Vries, its architecture and decoration form part of a long tradition of symbolism and myth woven into the plan and fabric of the building. And the driver behind this was the cult of sovereignty – an expression of wealth, stability and control in times that were anything but stable.

These were tumultuous decades: religious reformation, scientific upheaval, the stirrings of empire. In such a shifting landscape, buildings like Wollaton offered something solid – an immersive and all-encompassing story in stone.

The ceiling at the top of the south stairwell is part of that story. Painted in the early 18th century, it depicts the Creation of Pandora. According to the tale, Pandora was created by the gods and gifted to humanity. She arrives with a jar (later corrupted into box) which, once opened, releases all the evils of the world. But at the very bottom, one thing remains inside: hope.

The way the ceiling is painted in a luminous trompe l’œil adds another storied layer for me. When I look up at it, I feel as though I’m part of the story. This isn’t detached art – it’s immersive. The more I look, the more I feel as though I’m becoming part of the drama. For me, it’s a way of experiencing something through observation, through involvement – not by standing back to observe the fact (an instagrammable historic ceiling), but by leaning in to absorb its fundamental truth: the idea of releasing powerful forces without fully understanding their consequences.

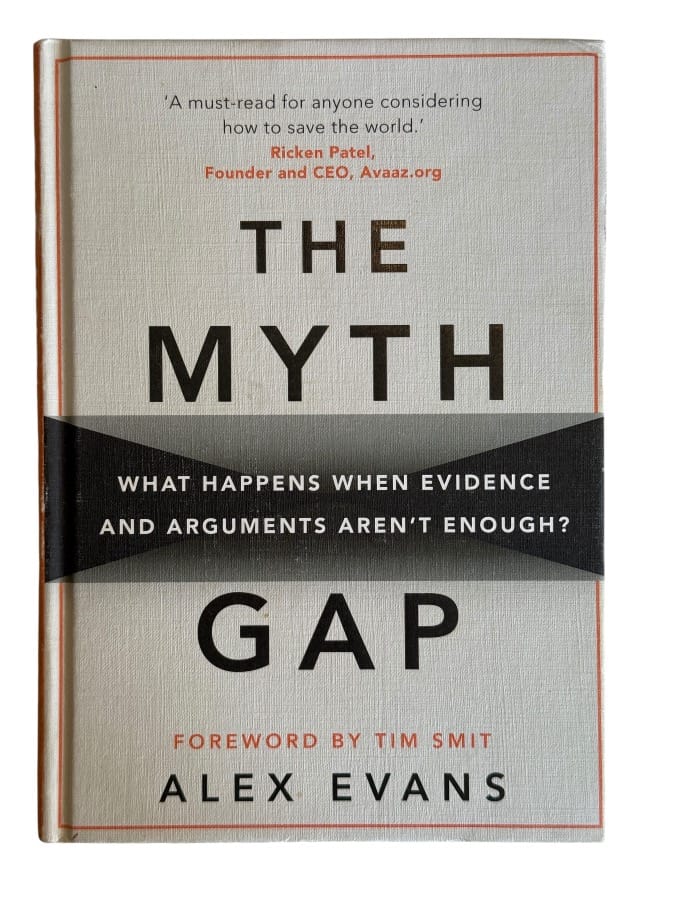

It wasn’t until I came across Alex Evans’ The Myth Gap that I fully understood why this way of observation helped so much. He introduces the idea that facts alone are not enough and that humans are storytelling animals – that the real drivers of change are to do with meaning, belonging and identity. In a world that is saturated with data and information, we are starved of meaning.

It was another writer, Aldous Huxley, who added an extra dimension to my understanding. He feared not a world where truth would be hidden, but one where it might promise us so much that it would be drowned in shallowness, apathy and inertia. A world full of smoke and mirrors, where we forget how to notice what really matters.

Lately, on my travels, I’ve noticed that the further I go into the past, the more it seems to nourish me. A kind of rooted nutrient. One that helps me look at the present from a balanced place.

It’s a different lens – one shaped not by urgency, but by continuity. And sometimes, when things feel particularly disjointed, when I feel adrift from a larger narrative, these places help me navigate. They remind me that meaning is something we can recover – not as nostalgia, but as an extension of Alex Evans’ insight and a counter-narrative to Aldous Huxley’s fears.

And that brings me back to the ceiling at Wollaton – and to the dedicated work of Marta and Ryan.

Because their work is not only about preserving paint on plaster. It is, in itself, a story. A slow, skilful and intentional act that keeps the past alive. One that allows us to draw from the deep well of myth, and re-shape and re-imagine the meaning behind those stories into our present – not as relics, but as guiding lights. Their work invites new eyes to engage with old meaning. It shows that myth still has relevance, and that there is care and continuity in a world that often feels unfeeling.

And for me, witnessing their work – being up there on that platform, lens in hand – felt like a special moment: a reminder that meaning is still being made. That we live in a society which, despite all its distractions, still makes space for this kind of care. That craftsmanship, attention, and respect for the past haven’t vanished.

For me, what Marta and Ryan represent is quite profound – the little kernel of hope that is left behind in Pandora’s jar after all else has gone.

Members can get up close and personal to the ceiling in a wonderful VR of the ceiling and conservation works here (viewable on any device):

I made a short video showing Marta and Ryan at work on the ceiling. Members can see it here:

This Digest is member-powered. If it brings you something of value, you’re warmly invited to join. 📸🏛🚐

Wollaton Hall

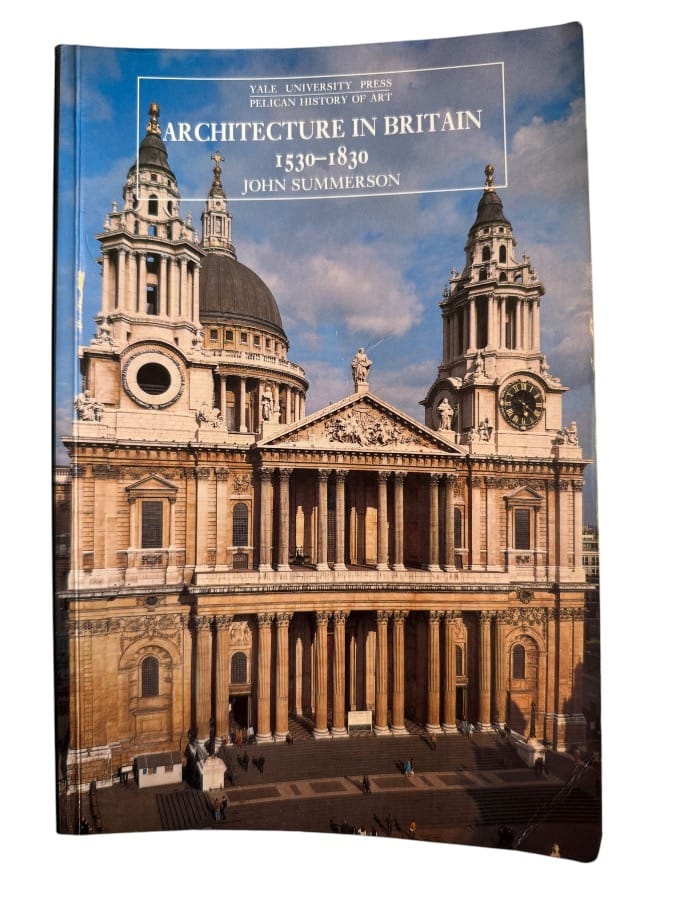

Walking around the beautiful grounds at Wollaton, it's hard to believe that this building is from the late C16th. Architect Robert Smythson was stone mason at Longleat and designed Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire. Architectural historian John Summerson says that Wollaton is his chief work.

Many of these buildings were built to recieve the Queen and her entourage as she journeyed from one place to another.

Wollaton Hall is open to the public - the grounds are beautiful and worth a visit.

Wollaton Hall was used as Wayne Manor in the Batman movie The Dark Knight Rises.

These conservators, these minimal interventionists, aren’t simply curators of the paint pot and infill, but also guardians of a rich cultural tapestry that teaches us what it means to be human.

I’ve photographed many projects where artists, artisans and conservators have helped restore—and sometimes transform—the memory of an age, an epithet, a story, a turning point, through a building, a memorial or a piece of art.

Adam is more than a bookbinder; he is a Time Lord, a guardian of this precious conduit to history, enshrining fragile hooks to the past with a love and dedication that has taken him over 14 years to hone.

I'm in Dorset at the studio of stained glass artist Tom Denny, spending the morning photographing him as he works on a new east window for St. John’s Church in Tisbury, Wiltshire.

Member's Field Notes

Where the lens lingers a little longer...

Pandora Ceiling in VR:

Video of Conservation of Pandora Ceiling:

Member Supplements - deep dives into the Digest

Comperandum's (a nod to Banister Fletcher)

Like to linger a little longer? Why not consider becoming a member and help me continue my journey.

Recent Digest Sponsors:

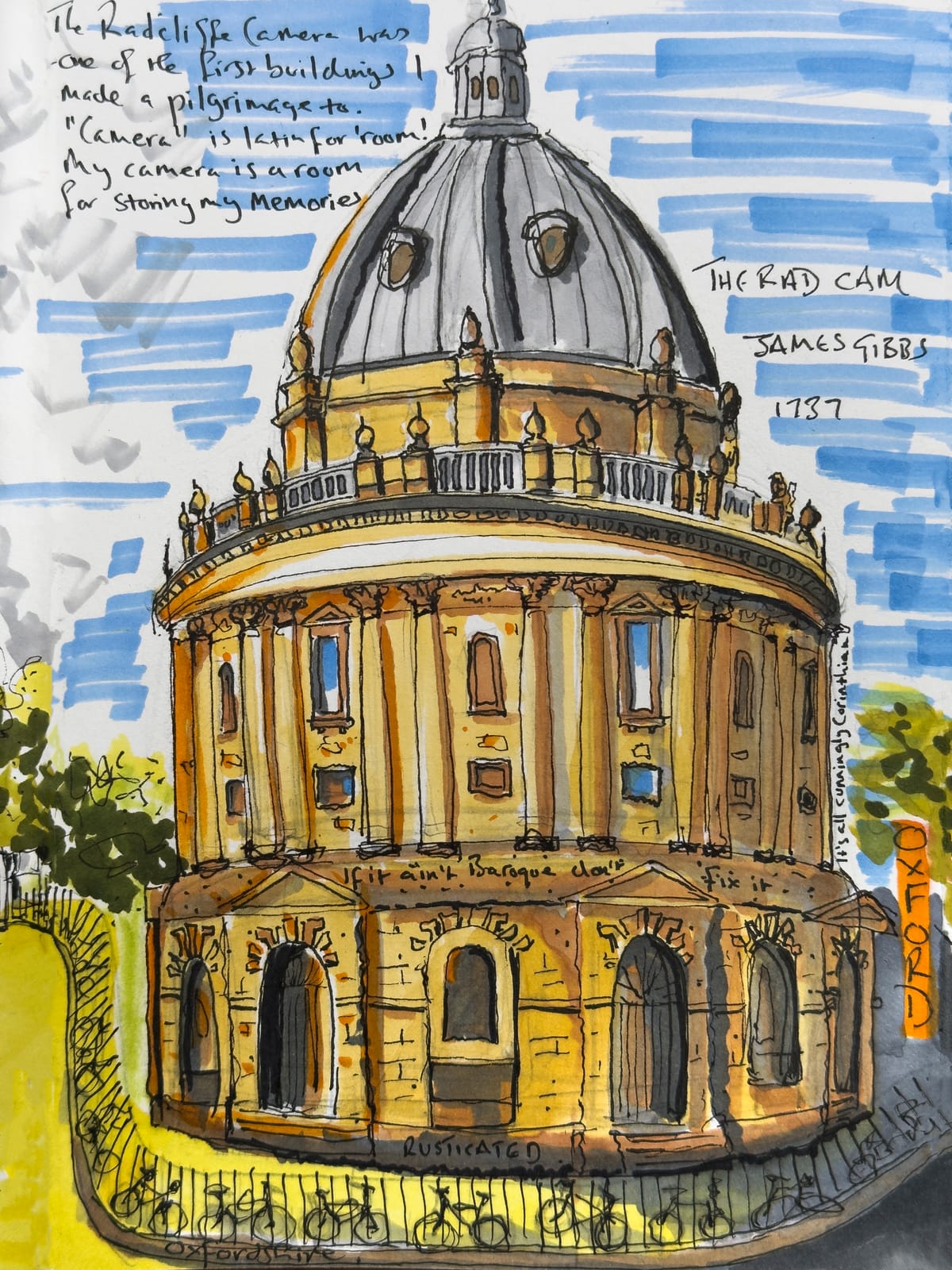

So proud to be involved with this project. In early July I will be taking students out around the streets of Haslingden and re-connecting them to place using my art as a guide.

Kind words from a subscriber:

Andy your work is becoming wonderful, remarkable. A so-called breakdown has been milled into its constituent parts, becoming profound construction: through perception, architecture, the lens and the pen. In your Repton crypt essay a deep description of our social anxiety - and our reason to be....

I know these are difficult times, but if my work has resonated with you – through words, photographs or drawings – and you’re in a position to support it, I’d be deeply grateful.

Becoming a member helps me keep the arts alive – and enables me to offer free photography to places like Burford, preserving their stories for future generations.

You can also make a donation, or purchase a piece of my art – each option plays a part in keeping this work going.

Thank you – for reading, for sharing, and for being part of this journey.

Become a Member:

Make a Donation:

Purchase Art:

Companies can sponsor me too - more here:

Kind words from Bluesky:

Thank You!

Photographs and words by Andy Marshall (unless otherwise stated). Most photographs are taken with Iphone 16 Pro and DJI Mini 3 Pro.

Member discussion